Data Analysis: Regional Inequalities in Chinese College Admissions

Jun 7, 2018 · 1025 words · 5-minute read

Five years ago, with the help of two wonderful editors, I wrote about the drastic differences in admissions quotas Chinese universities set for different provinces. All the arguments made in the article are still true today, but I was fortunate to obtain a better set of data recently (eight years of enrollment numbers from Tsinghua, one of China’s preeminent universities). And armed with some improved visualization skills, I hope to illustrate below, with more clarity, the regional inequalities in China’s elite college admissions.

Every June, students from around the country take the gaokao, the College Entrance Exam, in the province of their household registration. Crucially, each province administers its own exam, so the gaokao is not a uniform, nationwide test, unlike the SATs or the ACTs in the U.S., or the A-levels in the U.K. Prior to the gaokao, universities set quotas for each province and later admit all top scorers who expressed interest in their institution. Universities also run guaranteed admissions programs targeting Olympiad winners, foreign language-speakers, athletes, etc., though the proportion of students admitted primarily for non-academic reasons is much smaller than that at U.S. colleges.

Universities do not disclose how the seemingly arbitrary quota is determined for each province. Due to the hybrid nature of the admissions scheme, nor do we know how many students from each province get into top universities, either through the regular gaokao or through the guaranteed admissions programs. (Since Chinese students do not “apply” to multiple universities in the sense that American or British students do, I use the words “admit/admission” and “enroll/enrollment” interchangeably.)

Tsinghua, together with Peking University, are arguably China’s most prestigious institutions. However, as Professor Zhang Qianfan of Peking University Law School pointed out, their elite status is the product of administrative engineering – the national government divides universities into tiers and pours significantly more money into a select few in order to, in the most recent development plan’s language, “create world class universities by the end of 2050.”

Thus, it is no surprise that Tsinghua boasts some of the country’s best education resources and that a spot at Tsinghua is the most coveted prize for high school graduates.

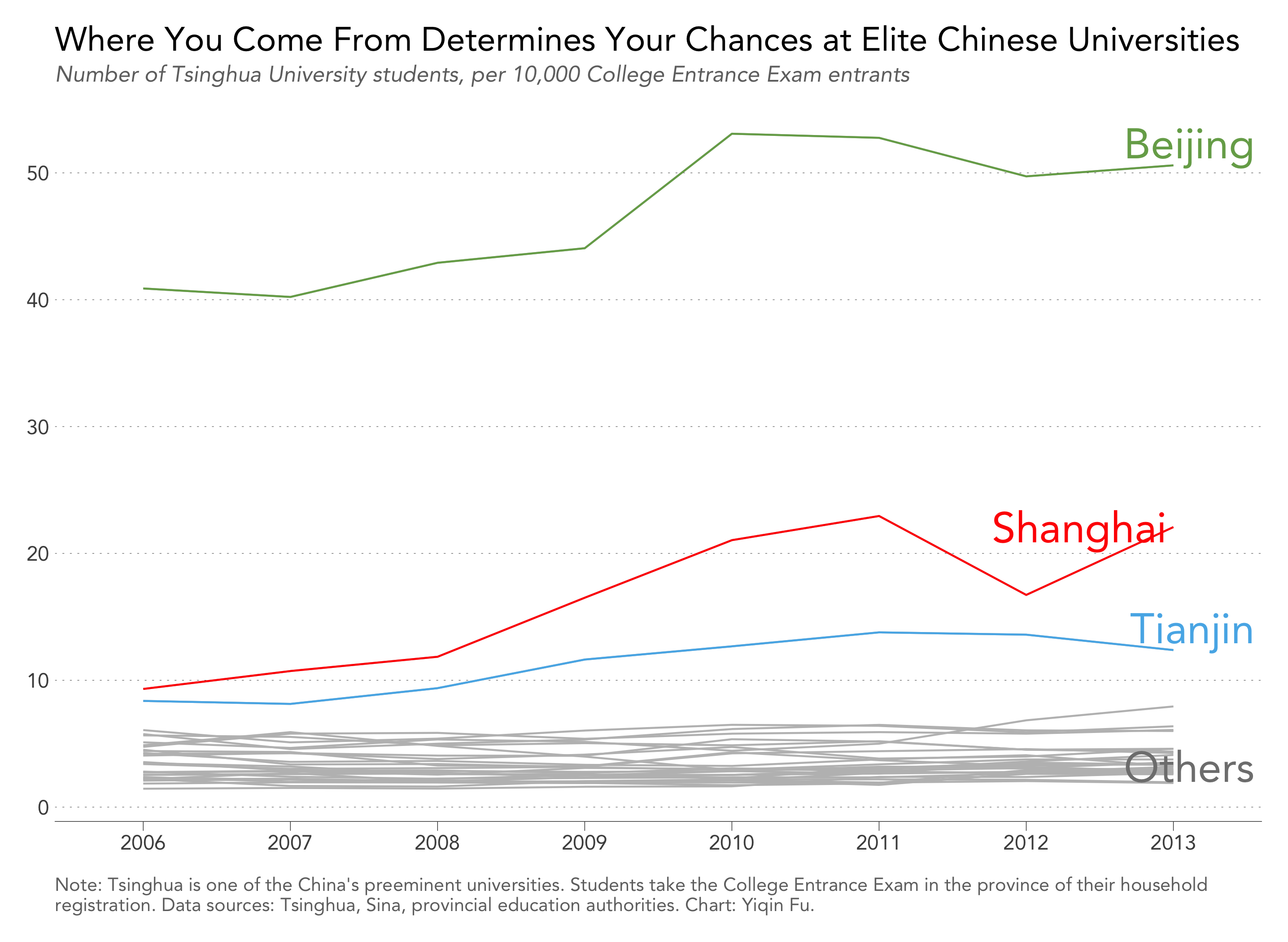

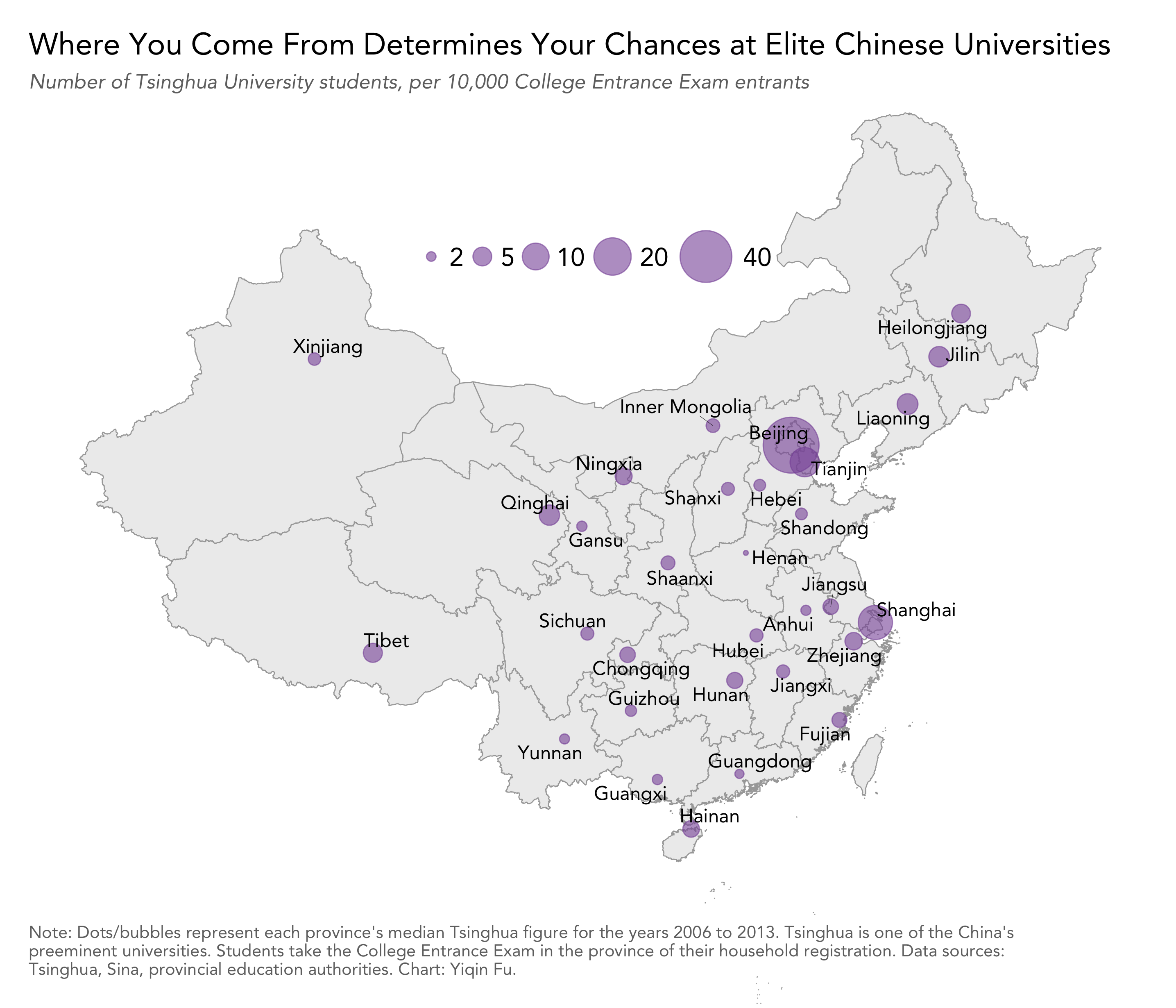

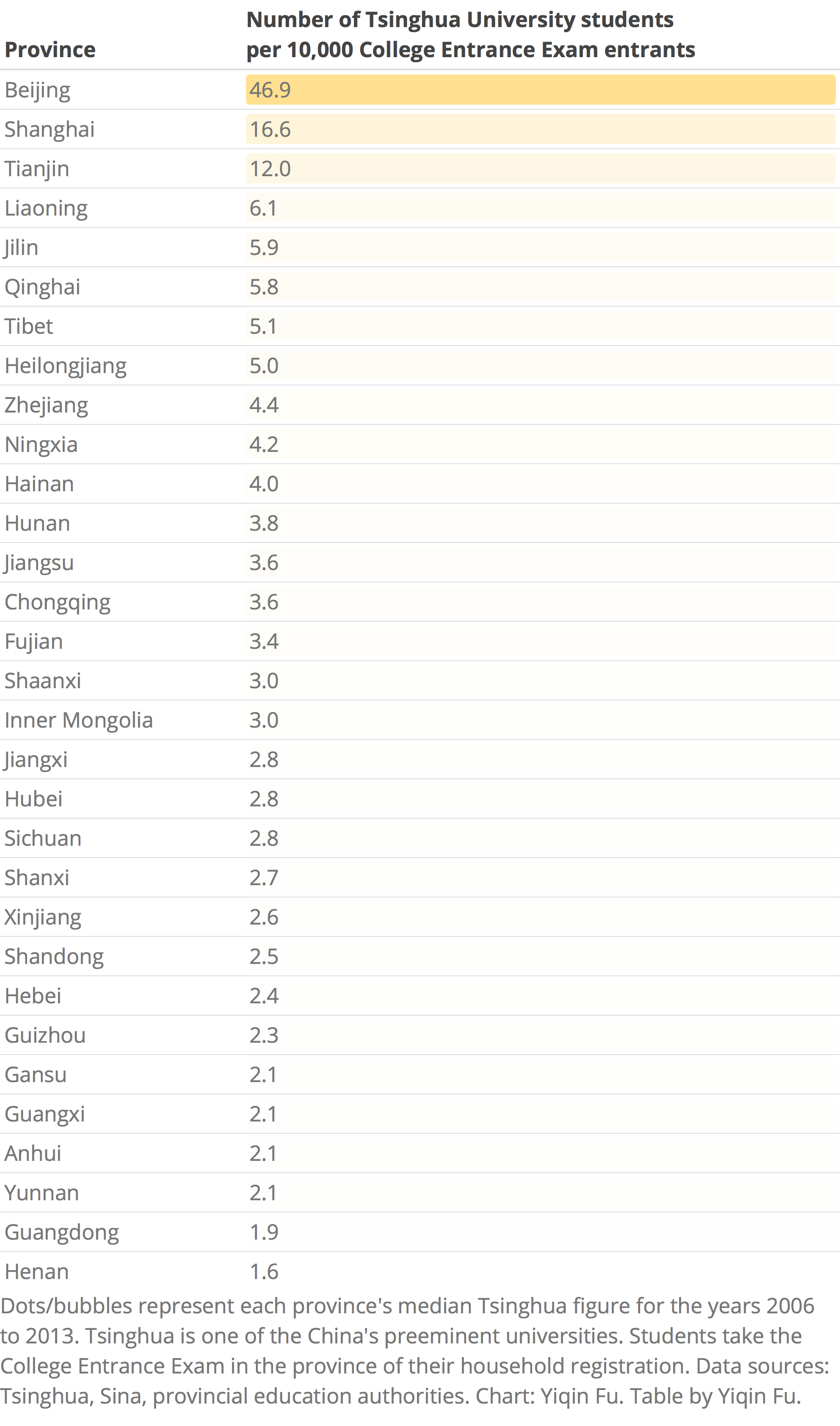

I obtained eight years of Tsinghua enrollment data (student rosters from 2006 to 2013) and found that Beijing students are 30 times more likely than students from neighboring Henan to attend Tsinghua. (Migrant children who study in Beijing without local household registration must return to their home province to take the gaokao.)

I also find that the actual number of students attending Tsinghua from each province differs significantly from what is reported by the media. First, the quotas universities publish only concern the gaokao admits, not those that went through the guaranteed admissions programs. Thus, the published quotas disproportionally undercount the number of acceptances in wealthier provinces, since wealthier provinces are more likely to produce Olympiad winners, foreign language-speakers, etc. Second, universities also exercise discretion in following the published quotas. For example, Tsinghua routinely admits more top scorers in some provinces than the quotas would allow.

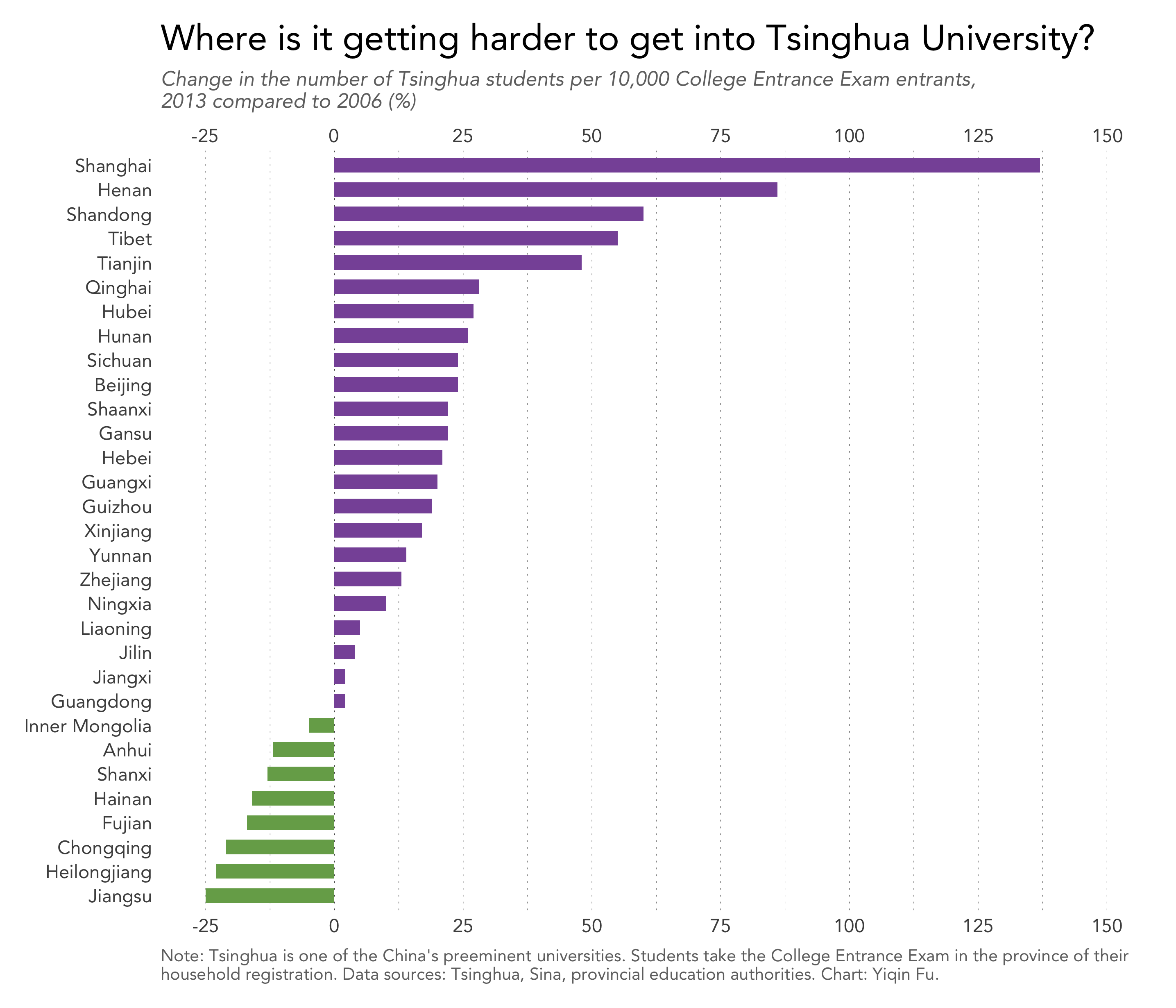

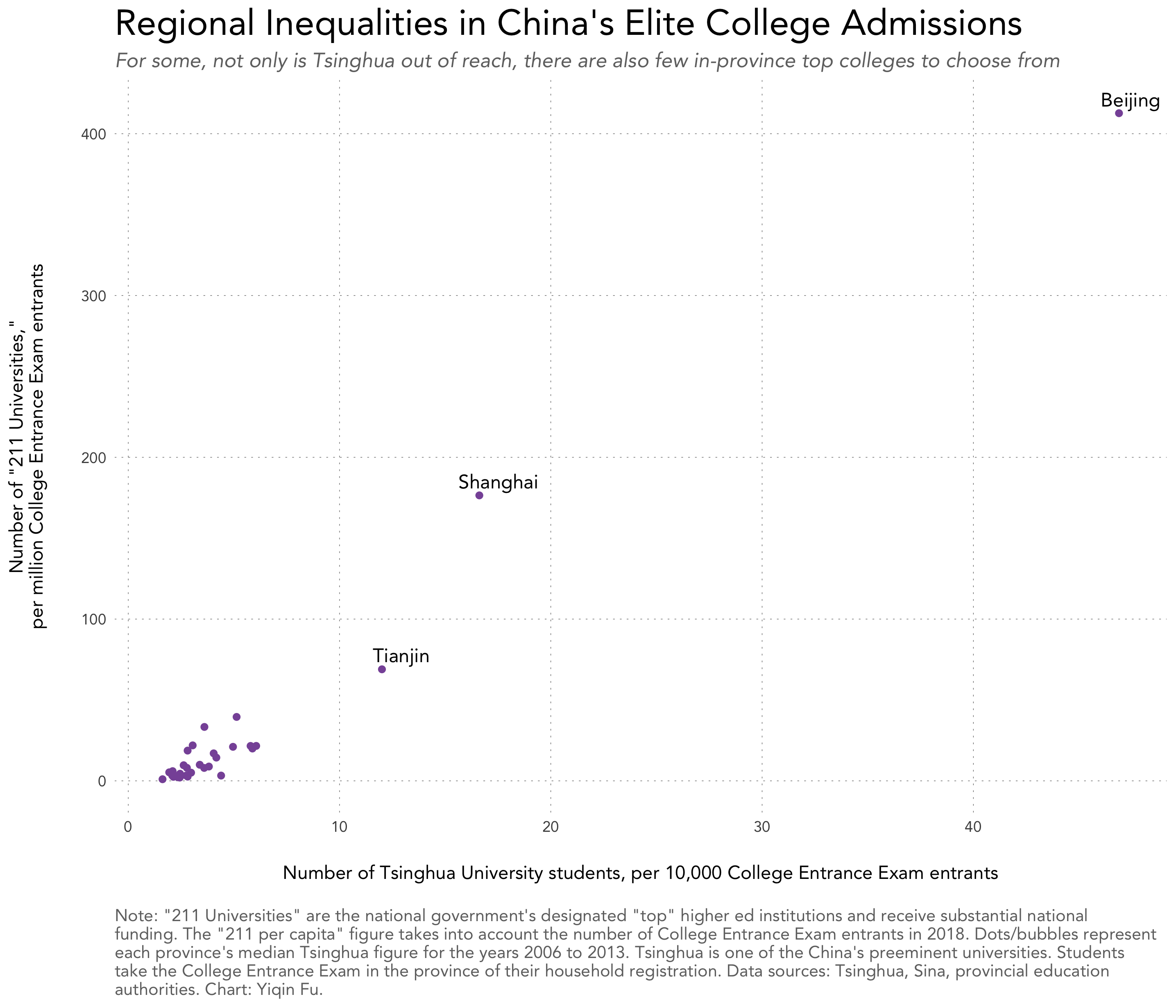

It is a shame that Tsinghua (and other universities) do not make any enrollment data public, not even simple breakdowns by gender or province. For illustration purposes, though, the eight years of data charted here is sufficient to show that students from metropolitan Beijing, Shanghai, and Tianjin face a far less competitive environment than their countrymen from neighboring provinces.

Some have pointed out that all colleges, not just Tsinghua, practice “local protectionism” to a certain extent. Thus, students theoretically all enjoy the same home advantage. But even then, there are still plenty of reasons to be concerned about the vast regional inequalities in elite college admissions.

First, Tsinghua is likely allocated far more funding by the national government than other universities are and thus bears more responsibility to accept top students from around the country. Although Tsinghua does not disclose the national vs. local breakdown of its revenue, other related statistics may shed some light on the amount of national funds it receives. A disclosure form filed by similarly-ranked Fudan University shows that the ratio of its national vs. local funding was 4:1 in 2011. In addition, after China announced its “world class 2050” development plan in 2017, Tsinghua’s total funding (national or local) jumped by 67%.

Second, not every province has good universities, and thus not every student has the home advantage Beijing students enjoy. In the chart below, the x-axis is still the Tsinghua admissions figure, and the y-axis is now the number of “211 Universities” per million students. “211 Universities” are a group of 112 higher education institutions designated as “top” by the Ministry of Education.

Evidently, Beijing, Shanghai, and Tianjin stand out on both dimensions. In other words, it is not only relatively easy for Shanghai students to get into Tsinghua, they also have many top universities in their own area to choose from.

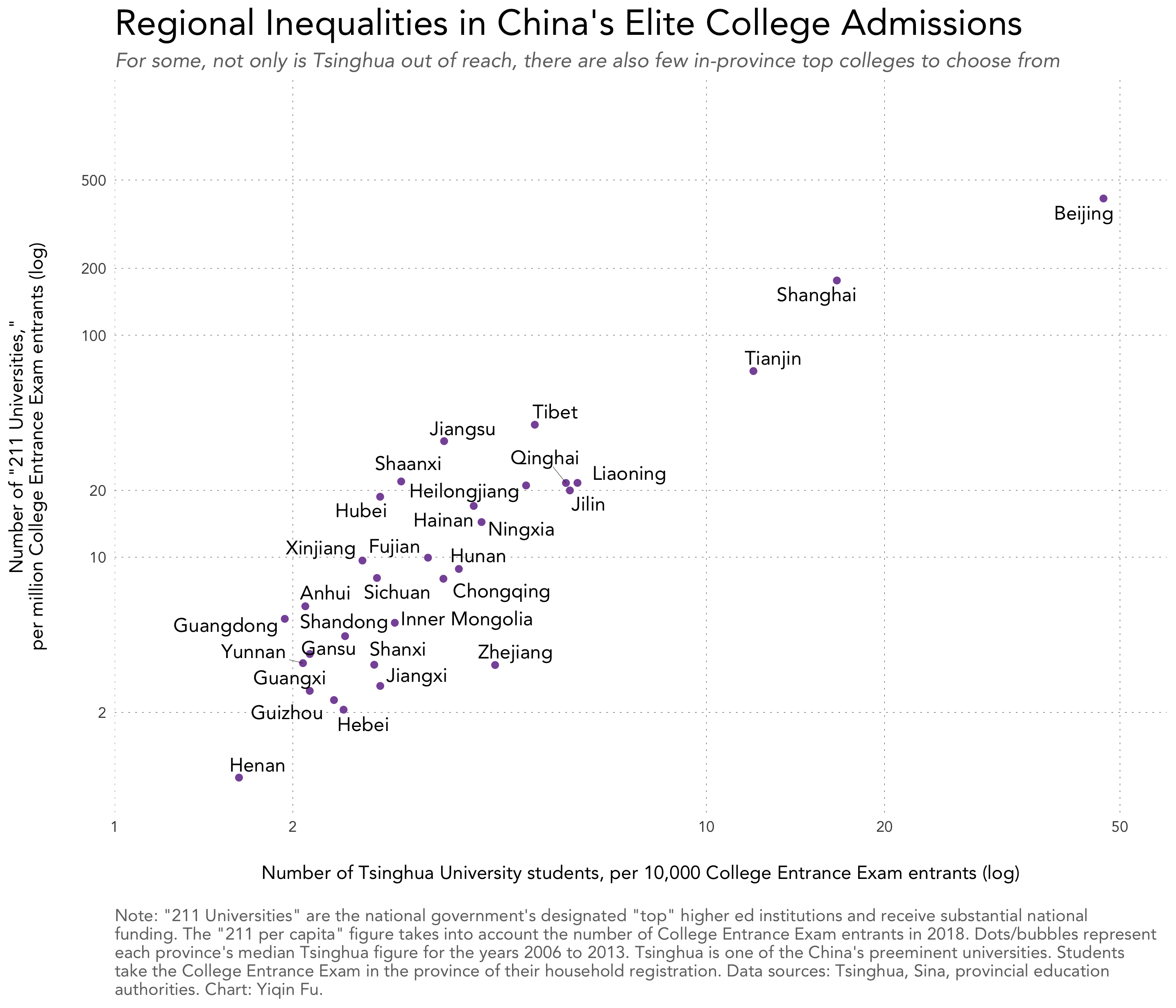

Students from other provinces face such a different environment that we have to take the log of both scales in order see all the provinces on the chart.

As shown below, Jiangsu students are still relatively lucky, for although it is hard to for them to get into Tsinghua, they have a few choices at home. Henan students, on the other hand, not only face the steepest competition at Tsinghua, but also have close to no top university in their own province.

Distribution of scarce, quality education resources is universal problem faced by all countries and all education systems. Even the U.S. and the U.K., with far more abundant higher education resources than China, still face criticisms of racial discrimination, class discrimination, and nepotism in their college admissions practices. Given that it is impossible to come up with a fairer policy overnight, Chinese universities can perhaps start by communicating to the public their rationale behind each year’s quota.

(A Chinese version of this article was published on June 8 by the Financial Times' Chinese edition.

Many thanks to David Wertime, Liz Carter, and Rachel Lu at Tea Leaf Nation for helping me with the original article, and to Silva Shih at the FT Chinese for her feedback on the new version.)