Fame and Influence Across Five Millennia

Jun 18, 2021 · 4343 words · 21-minute read

Who are the most influential people in the history of the world?

I think about this question a lot because different historical circumstances give rise to different types of heroes (or villains). For example, the rise and fall of religion, prolonged periods of interstate warfare, and changing media technologies each allowed people with drastically different skills and personalities to rise to prominence. Thus, mapping out who gains fame (or notoriety) when would help us understand the evolution of human society.1

Aside from intellectual curiosity, I’m also motivated by self-interest: For those living in the early 21st century that wish to leave something behind, who are the people they ought to look up to? What did those people do, and for what are they remembered?

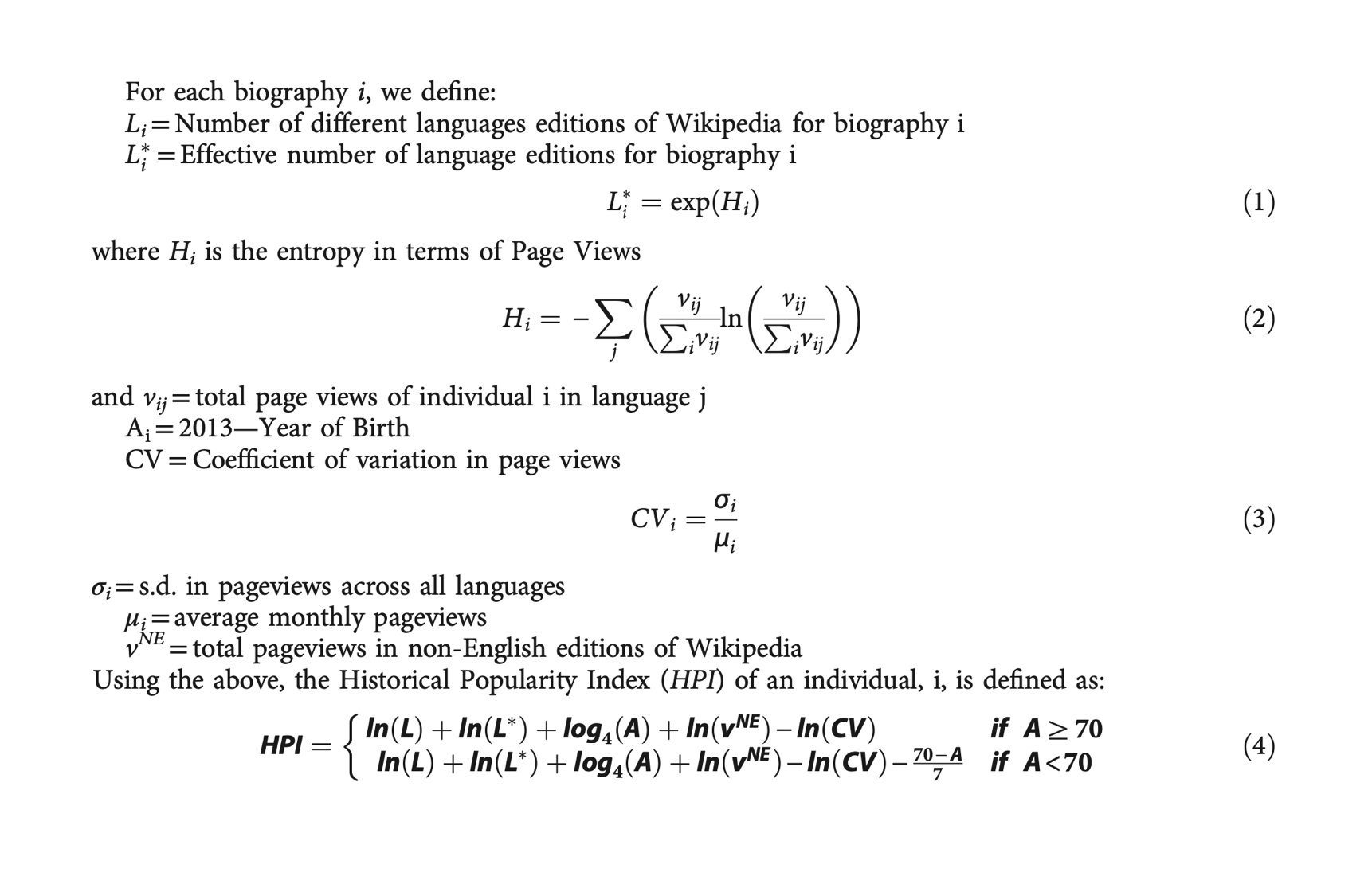

The MIT Media Lab’s Wikipedia-Based Approach

The MIT Media Lab’s Pantheon project provides an excellent dataset to answer this question. Using browsing data on Wikipedia biographies, a large team of Media Lab researchers constructed a measure of fame called the Historical Popularity Index (HPI). The index takes five inputs: (1) the number of Wikipedia language editions of a given individual’s page, (2) the total number of pageviews across all editions, (3) the dispersion of pageviews across time and (4) across language editions, as well as (5) the individual’s year of birth.2 In other words, the longer you’ve been around, the more language editions there are of your biography, the more your biographies are viewed, the more “stable” the pageviews are across time and language, the higher your HPI will be.

Importantly, the HPI reflects how present people think about present and past people – the index captures retrospective fame for past people and contemporaneous fame for present people. We will return to the biases the measure introduces in a later section.

Here are the “most famous individuals” in the history of the world:

| Rank | Name | HPI | Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Muhammad | 100 | religious figures |

| 2 | Genghis Khan | 98 | military personnel |

| 3 | Leonardo da Vinci | 97 | designers, inventors |

| 4 | Isaac Newton | 97 | mathematicians, natural scientists |

| 5 | Ludwig van Beethoven | 97 | musicians |

| 6 | Alexander the Great | 96 | military personnel |

| 7 | Aristotle | 96 | humanities and social science scholars |

| 8 | Napolean | 96 | politicians |

| 9 | Julius Caesar | 96 | politicians |

| 10 | Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart | 96 | musicians |

On the project’s official website, you can view individual rankings and filter by region, time period, and occupation. However, some summary statistics is needed if we want to see aggregate patterns in the types of individuals that rise to prominence under different historical circumstances.

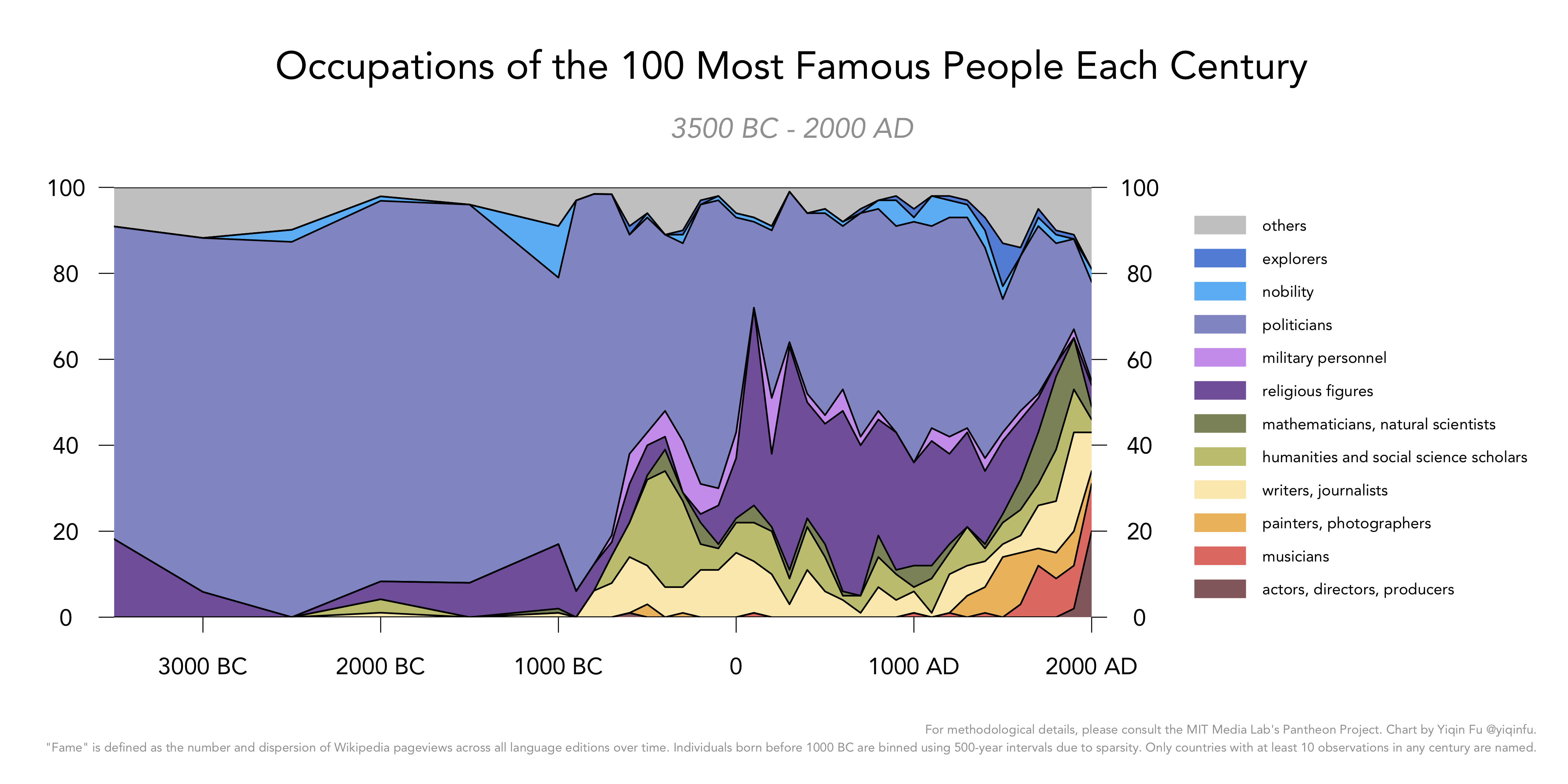

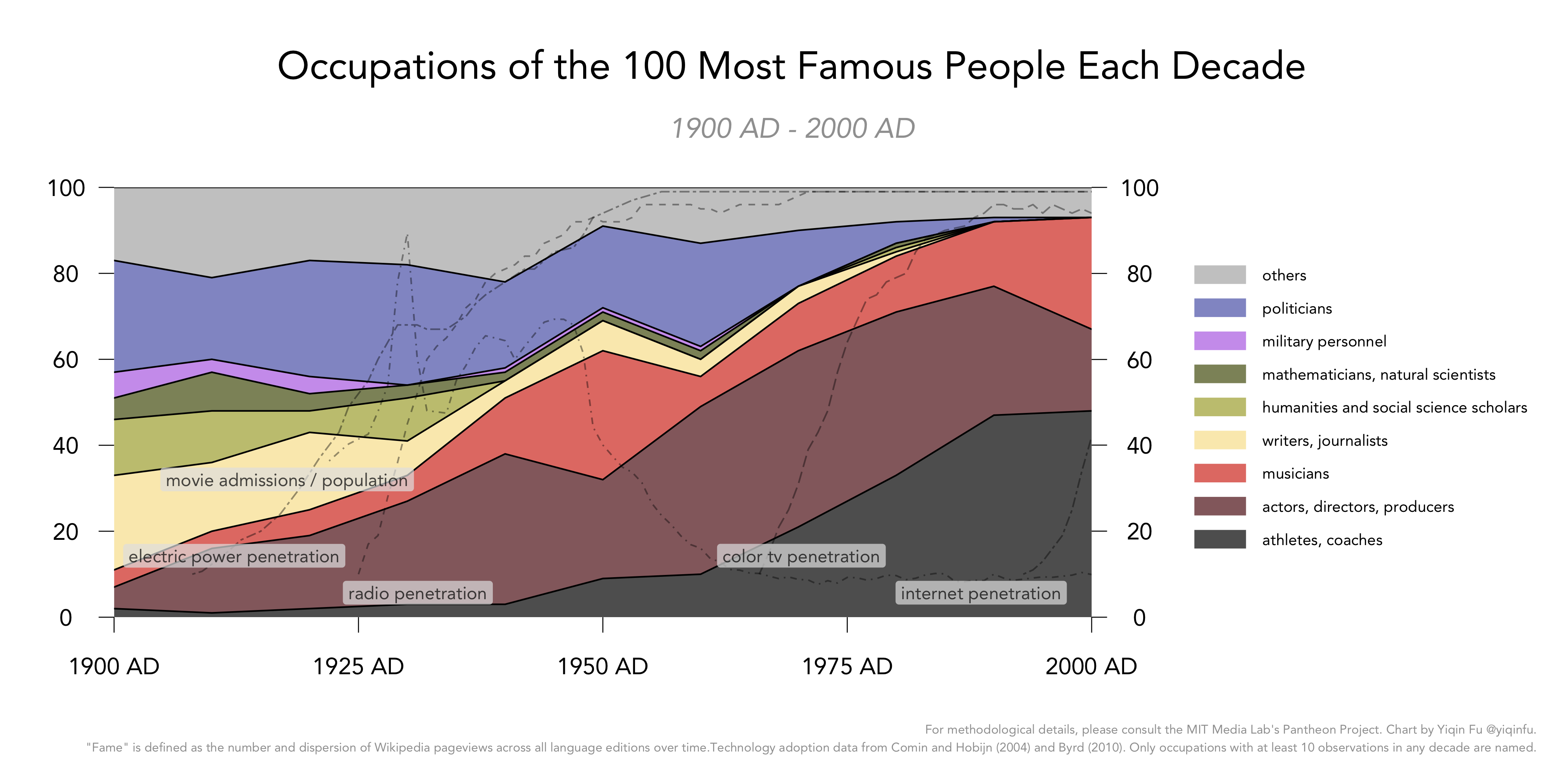

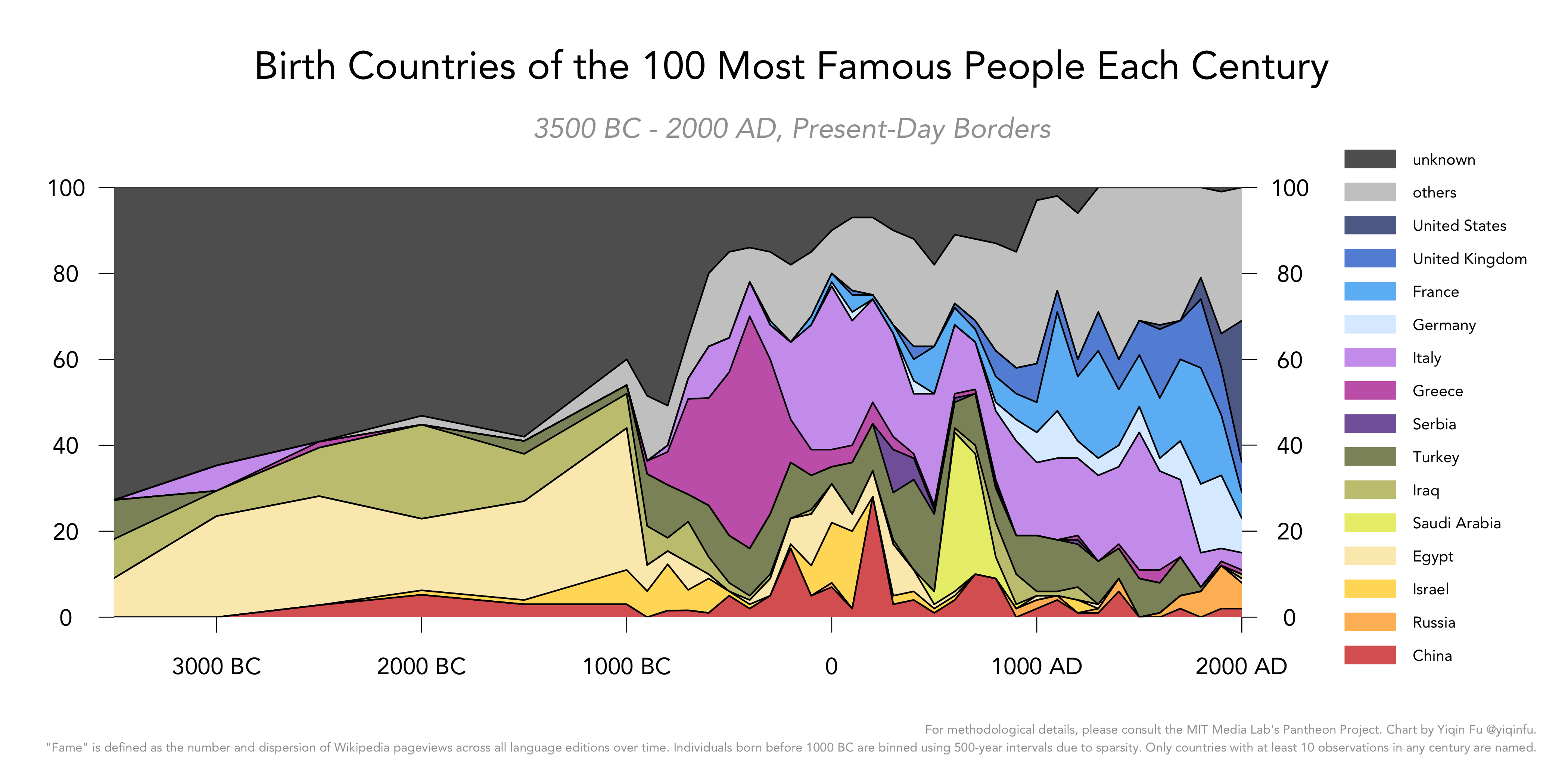

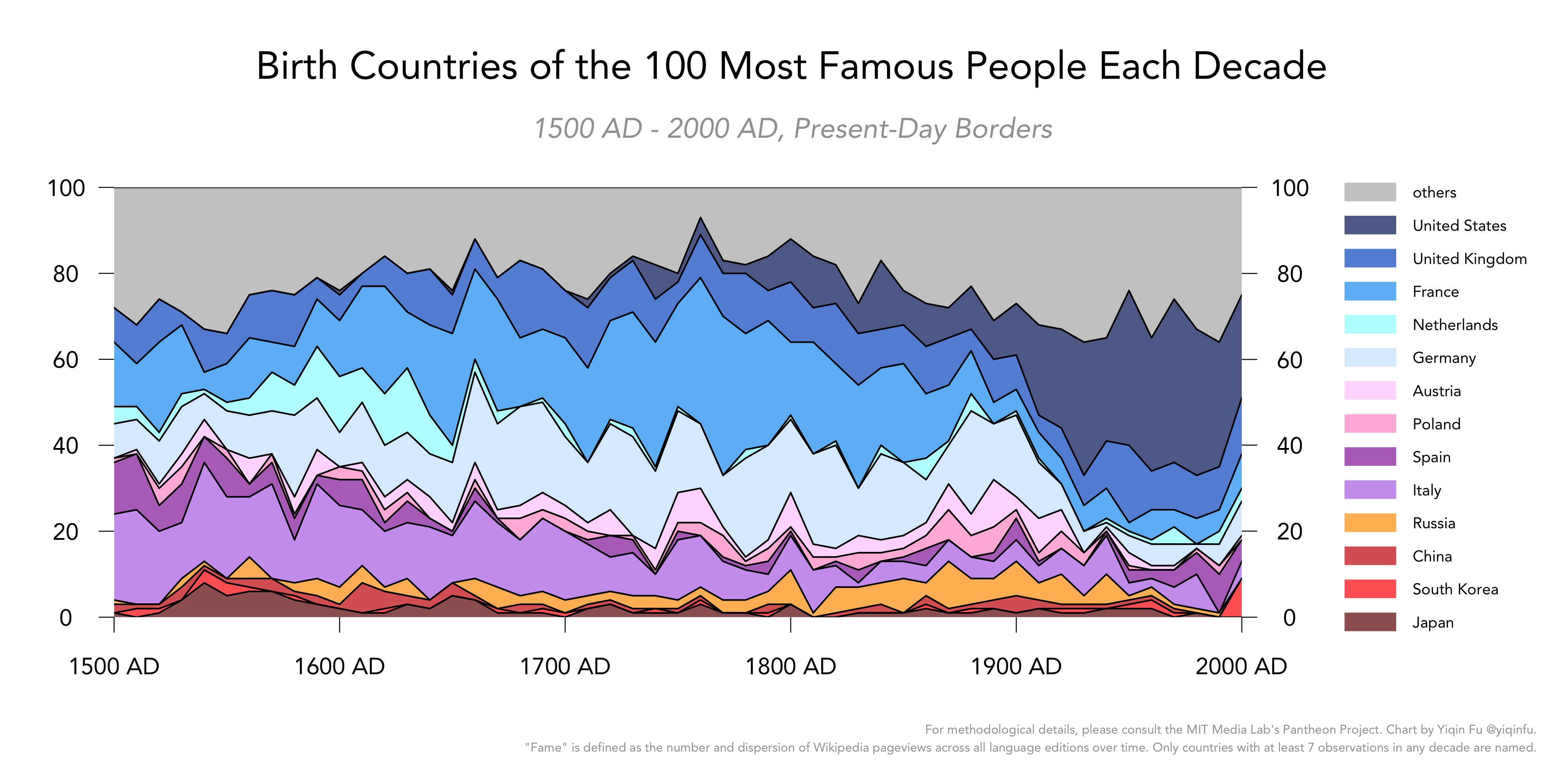

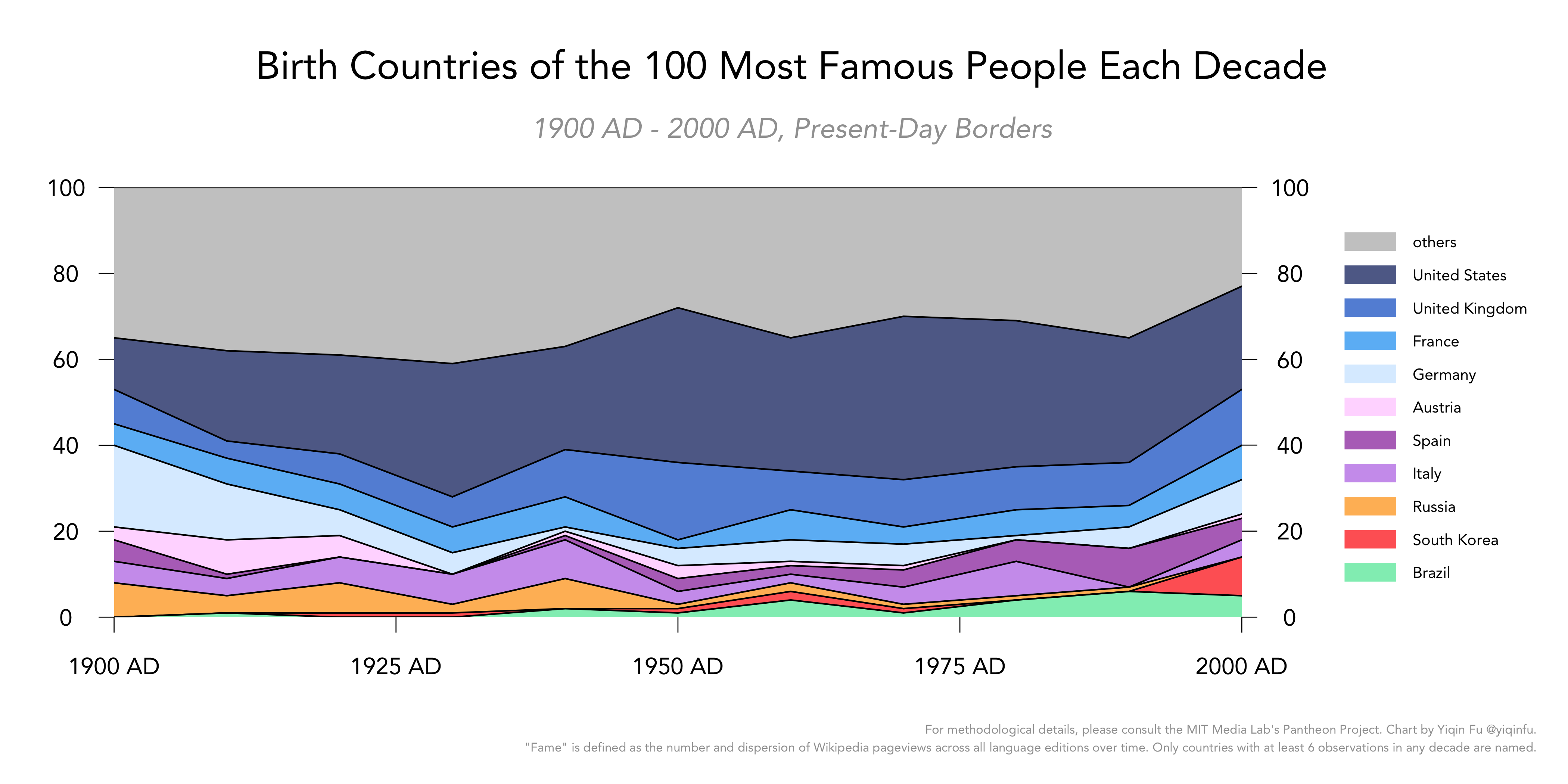

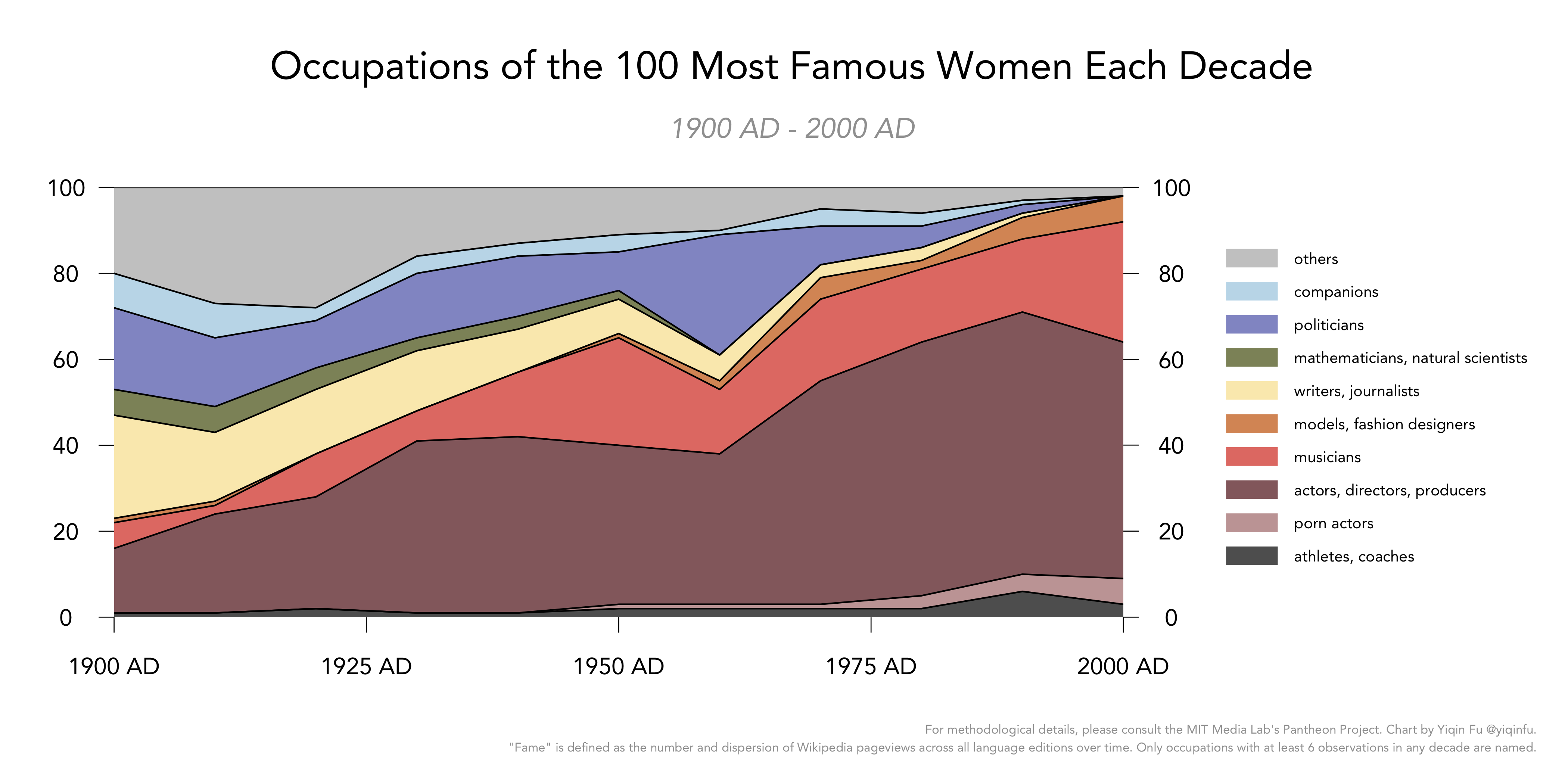

This blog post aims to fill that gap: First, I plot the “occupations” of the 100 “most famous people” by century and by decade. I show the distribution for three periods: 3500 BC to 2000 AD (five millennia), 1500 AD to 2000 AD (early modern to contemporary), and 1900 AD to 2000 AD (the last century). Separately, I plot the geographic distribution of the “famous” individuals, both to show the historical shifts in the cultural centers of the world and to show Wikipedia’s Eurocentric nature. Last, I subset the data to women and explore the changing roles of prominent women over time.

Occupations by Century and Decade

To show historical shifts in the types of individuals that rise to prominence, I create crude occupation categories such as “musicians” (including both Mozart and Aretha Franklin) and “humanities and social science scholars” (philosophers, economists, etc.). Noteworthy individuals often work in multiple fields, but for simplicity’s sake, each person has only one assigned occupation in the dataset.

I bin all individuals by their years of birth and plot the occupations of the 100 most famous people in each century, starting from 3500 BC. (The data on individuals born before 1000 BC is sparse, so I bin by 500-year intervals as opposed to 100.)

I see three distinct periods in human history:

- War (3500 BC to 0);

- Religion and philosophy (500 BC to 1500 AD);

- Mass media (1500 AD to today).

Politicians form the largest category in almost all periods of human history, although they were the most dominant before the dawn of religion and mass media. Hammurabi (1810 BC - 1750 BC), Hannibal (247 BC - 183 BC), Alexander the Great (356 BC - 323 BC), and Augustus (63 BC - 14 AD) are all high-HPI individuals that made their name through conquest.

Politicians' relative fame and influence waned in the past few centuries, and the change might be for the better – Most of us live in peaceful and prosperous societies and get to obsess over actors instead (see the recent rise of the actor class on the chart).

500 BC was the golden age of philosophers (light green on the chart) – Socrates (470 BC - 399 BC) and Plato (428 BC - 348 BC) in the West, Confucius (551 BC - 479 BC) and Laozi (around 500 BC) in the East. The era of philosophers coincided with the rise of military personnel (light purple on the chart). The relationship here may be causal – As city states were consolidated into empires, both the rulers and the people needed political philosophers, and philosophers had a lot more to draw inspiration from compared to before.

Religion dominated the Middle Ages (dark purple on the chart), and its fall coincided with the rise of Enlightenment-era scientists (definitely a causal relationship here).

Painters (orange on the chart) rose to prominence in the 15th and 16th centuries (Renaissance) but ceded ground not long after, likely to musicians and actors, who produced higher dimensional work that had a stronger visual impact.

Let’s zoom in and look at the modern period more closely.

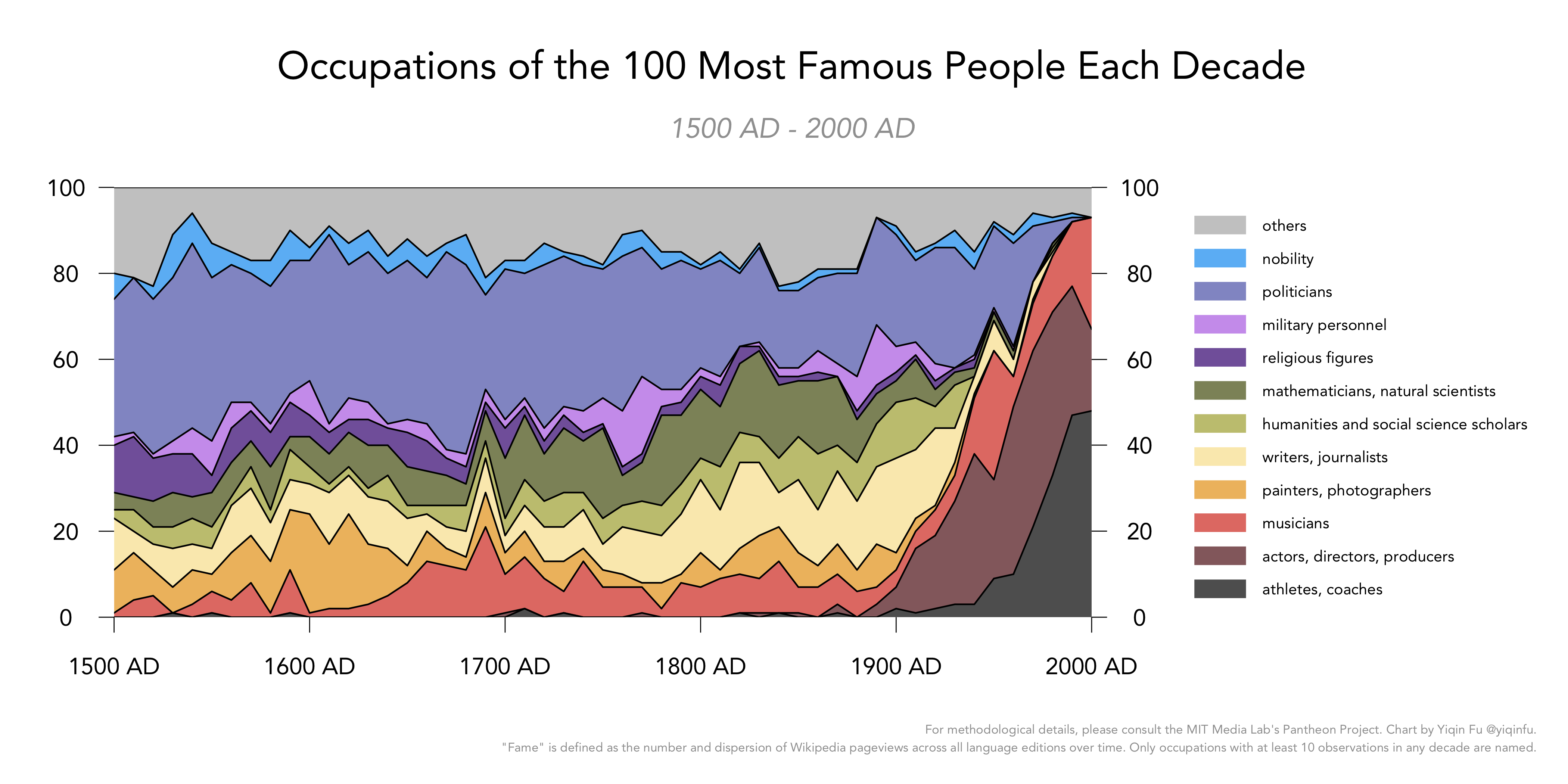

The story here is largely the same: The decline of the politician class (blue), the extinction of religious leaders (dark purple), the rise of scientists (dark green), the rise and fall of painters (orange), the enduring appeal of musicians (here defined as anyone that sings, plays, or composes music), and the sharp rise of film people (red) and sportspeople (black).

To get a better sense of the dramatic cultural shifts in the 20th century, we zoom in again:

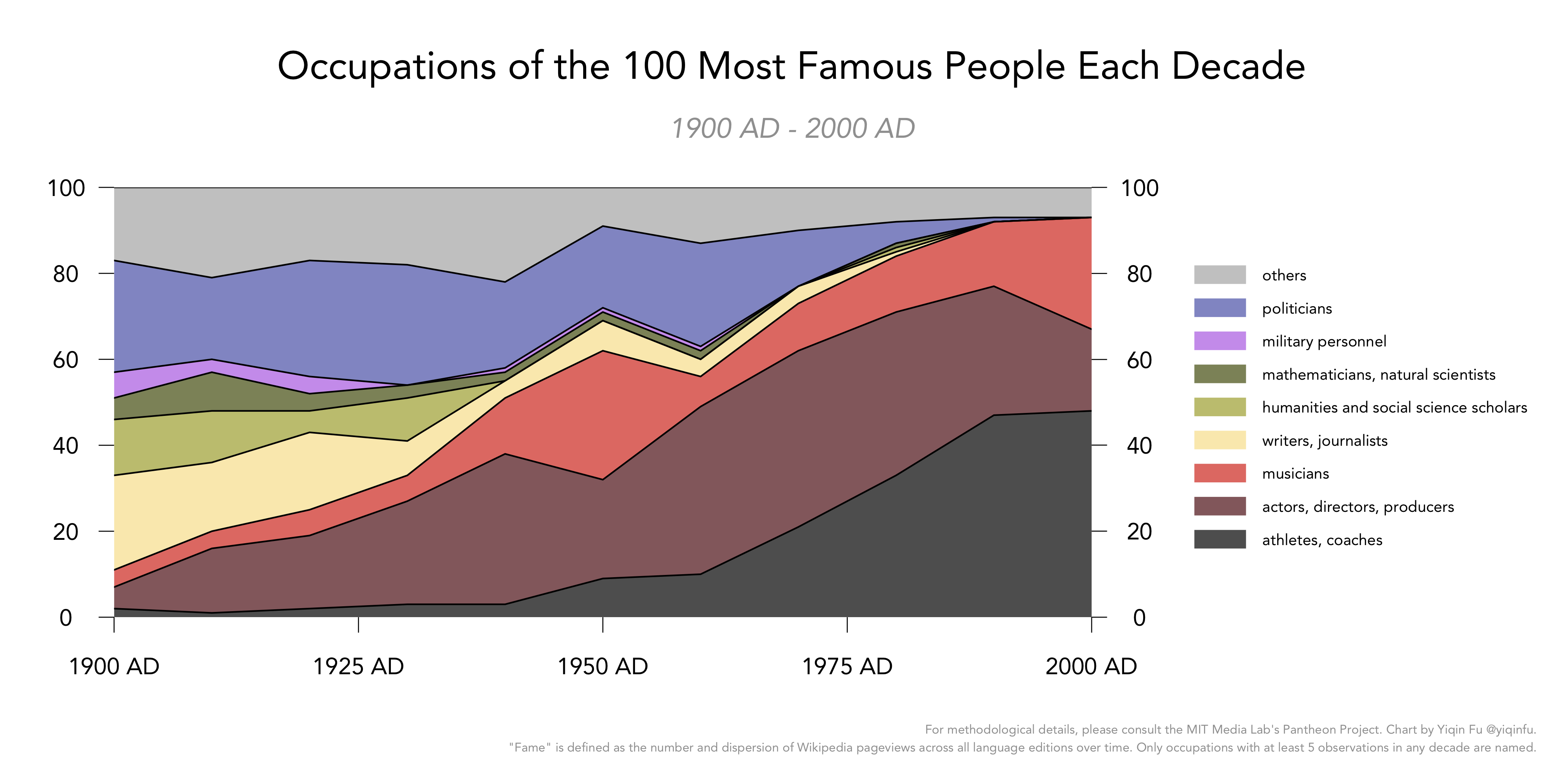

Nobility (light blue) and religious figures (dark purple) have disappeared entirely in this period. Military leaders (light purple) as well as writers (yellow) and thinkers (light green) were prominent in the years of war but quickly lost to athletes, actors, and musicians.

Is the dominance of athletes, actors, and musicians permanent or temporary?

As many as 70% to 90% of famous individuals born after the 1960s work in the entertainment industry (sports, music, film and television). These three occupations make up only 10% of famous individuals born in the 1900s. Is the shift towards entertainment permanent or temporary?

In public health and social science, researchers distinguish between age and cohort effects. There are reasons to think that the age is effect is at work – the share of athletes and actors for this decade will go down as we move further away. After all, athletes, actors, and musicians peak early (usually in their 20s and 30s), whereas politicians and writers today don’t have much credibility until age 40 or 50. When people in the 22nd century look back on the 1990s and the 2000s, perhaps actors and athletes won’t make up most of the names that come to mind.

However, I’d say that the evidence for cohort effects (or the “permanent shift hypothesis”) is stronger – the dominance of musicians, actors, and athletes is here to stay because they already make up 60% of “famous” people born in the 1950s. Fans that grew up with those celebrities would have been 80 or 90 years old now (and thus wouldn’t be contributing much to the celebrities' Wikipedia traffic), yet athletes, actors, and musicians still form the largest category for the decade 1950.

Another piece of evidence for the “permanent shift” hypothesis is that the rise of athletes, actors, and musicians almost perfectly tracks the penetration of radio, film, and color television in the U.S. Below I plot U.S. movie attendance and the penetration of various media technologies in dotted lines.

The marginal cost of content distribution fell dramatically in the era of mass media, so the content producers of the 20th and the 21st century can reach large audiences that only kings and emperors in previous periods could reach (through conquest).

The reason that the content producers of our century happen to be athletes, actors, and musicians is twofold. First, religion became extinct in much of the developed world after the scientific revolution, so few prominent content producers are religious figures. Second, the moving image makes a stronger impact on the audience compared to the written word or the static image. As consumer preferences shift, producers are also incentivized to move to fields that allow their work to scale. A Charles Dickens of the 1990s might give up novel writing for scriptwriting; a Monet of the 2000s may switch to cinematography.

In addition to changing consumer and producer preferences, mass media (especially the Internet) also changed how history is recorded. Web traffic to historical figures' Wikipedia pages is a function of not only the individuals' contemporaneous reach but also the consistency with which their names are mentioned throughout later generations.

And who shaped the historical narratives for much of human history? Those that held political power; those that could read and write. Perhaps the filtering done by the political and intellectual elites prevented a lot of contemporaneously popular material from entering our collective memory.

The thought experiment here is that if our visits to Wikipedia, ESPN, Netflix, IMDb, YouTube, and Spotify left no traces behind, and aliens had to reconstruct the culture of our time from the pages of The New Yorker, they might erroneously conclude that The Wire was the most “famous” tv show of the 2000s.

In other words, not only did television, film, and the Internet remove the gatekeepers in production and distribution, it also removed those in record-keeping – History is no longer chronicled by elites; it is recorded in real time and instantly fed to future people’s consumption decisions and the producers' production decisions.

Democratization of culture or amusing ourselves to death?

If athletes, actors, and musicians are here to stay, should we be celebrating the democratization of culture or its slow but dramatic demise? The answer, like the answers to all big questions, is probably somewhere in between.

On the one hand, an unprecedented number of people are producing culture. One no longer needs to be born into particular families or pay for years of training. As consumers, we also gain instant access to the world’s complete historical catalog, a treat that no power or wealth could have brought you in previous decades. More importantly, many of us live in such a peaceful and prosperous world that we get to idolize sports stars, actors, and YouTubers.

On the other hand, the dominance of the moving image – both due to its strong visual impact and its ability to scale via digital technologies – means that almost all of the world’s most famous people (both now and forever into the future?) will be athletes, actors, and musicians. Our children and grandchildren will grow up wanting to become one, and few names of scientists or writers will stick in our collective memory.

How concerned should we be? I think the ideal way to answer this question would be to compare the cultural diet of a median individual from the past to that of someone living today. The statistic Neil Postman cites in Amusing Ourselves to Death is that Thomas Paine’s Common Sense sold 400,000 copies in the late 1700s (in a population of three million), and the only cultural product with a similar level of popularity today would be the Super Bowl.

It’s hard to know if Postman is making an apt comparison here – Did the median person in colonial America really read and debate political philosophy all day? The literacy rate of men in Massachusetts and Connecticut was, according to Postman, somewhere between 89% and 95%. Should we be comparing that society with today’s America, let alone the world?

Any inter-temporal comparison we make runs into the following issues:

- What we are measuring has changed (fame and influence as recorded by elites –> fame recorded in real time);

- The pool of culture consumers has changed (literate, property owning white men –> pretty much everyone in the world)

- The medium of culture (or “influence”) production and distribution has changed (war, i.e. through physical contact –> religion, i.e. through oral storytelling –> music and video, i.e. digital)

We want to attribute all changes in the fame index to #3 (TV and the Internet made all of us dumb!), but it’s impossible to tease out the effects of #1 and #2.

Problems with the HPI

Besides the concern that we are comparing apples to oranges, we should also look at our measurement more closely – What if the HPI itself is flawed?

As economists would say: All indices are bad, but at least some are useful. I’ll be the first to admit that the index has many issues, but it is the best metric available that would allow us to take a long view at human history.

In the spirit of intellectual honesty, I’ll nonetheless outline below the issues I have with the HPI.

One major problem, as discussed above, is that the HPI captures contemporaneous fame for present individuals and retrospective fame for past individuals. Given that the “record-keeping” process has also changed thanks to new media technologies, comparing the composition of famous individuals across different centuries warrants caution.

Furthermore, I’ve identified four other issues that ought to be taken into account when interpreting the HPI. The first two concern the use of Wikipedia traffic as the underlying data source:

- Developed-world bias: Wikipedia is used more often in developed countries, so pageviews disproportionately reflect the interest of those living in richer countries. (Wikipedia is also blocked in China, which makes up 1/5 of the world’s population and 1/5 of the world’s online population.)

- Editor bias: Wikipedia editors skew English-speaking and male (90% male in a 2011 survey). While the HPI does not take into account the length or the quality of biographies, well-written and comprehensive entries are likely to attract more readers. Of the sportspeople that made my list of “100 most famous people by decade since 1500,” 6% are chess players. Of the actresses that made the women’s list, 3% are porn stars. I suspect the makeup of Wikipedia editors affected the type of biographies that got written and got written well, which in turn affected web traffic to those pages.

The other two issues I have with the index concern its specific formulation:

- European bias: By weighting all language editions equally, the HPI is implicitly favoring Europe – Europe has many small languages, whereas most of Latin America, South Asia, and East Asia have just one or two official languages.

- Present bias: The HPI rewards older individuals with a log function – those born earlier get a boost in the ranking. However, the boost for past people (or the discounting of present people) is not aggressive enough. In the 2020 edition of the dataset that we’re analyzing, Donald Trump (b. 1946) stands as the 17th most famous (or notorious) person ever, ahead of Bach (18th), Einstein (19th), Michelangelo (20th), Shakespeare (21st), and Martin Luther (22nd). Similarly, Anna Wintour (b. 1949) is listed as a “writer” with an HPI of 77, higher than that of Henry James (b. 1843, HPI 76) and George Eliot (b. 1819, HPI 74). While Trump and Wintour may end up getting more Wikipedia pageviews than Bach and Eliot in the long run, I think we should wait at least half a century after their deaths. The Pantheon HPI’s present bias means that comparisons between dead and living people ought to be treated with caution. In my analyses that bin individuals by decade, the problem can largely be ignored because we are only comparing individuals born in the same decade, but my century-level analyses and any comparison between two individuals' HPI would be heavily biased towards people living today.

If I get a chance to build my own index, I would 1) weigh the language editions by the number of speakers; 2) use a stepwise function to “punish” all living people and those that passed away within the past 50 years.

Countries of Birth by Century and Decade

Wikipedia’s Eurocentricity is evident in the geographic distribution of famous individuals' places of birth. Both historically and today, the vast majority of the world’s population have lived in Asia, but where the HPI is no longer sparse (after 1000 BC), we see mostly Europeans. Thus, it should be noted the HPI doesn’t measure how present people think of past and present people, but how present developed-world people think of past and present people.

With that caveat in mind, let’s look at the geographic distribution. Starting from 1000 BC when we start to have quality data, Greece, the Ottoman Empire, and Italy have dominated.3 I find the historical popularity of Italians particularly fascinating, because Italy’s share of global GDP never exceeded 5%, yet it was responsible for producing 20% of the world’s (or Europe’s) most famous individuals for 2,000 years!

Here is the list of the most famous Italians (people born in present-day Italy):

| Rank | Name | HPI | Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Leonardo da Vinci | 97 | designers, inventors |

| 2 | Julius Caesar | 96 | politicians |

| 3 | Galileo Galilei | 95 | mathematicians, natural scientists |

| 4 | Marco Polo | 95 | explorers |

| 5 | Michelangelo | 95 | painters, photographers |

| 6 | Christopher Columbus | 94 | explorers |

| 7 | Archimedes | 94 | mathematicians, natural scientists |

| 8 | Augustus | 93 | politicians |

| 9 | Dante Alighieri | 93 | writers, journalists |

| 10 | Raphael | 92 | painters, photographers |

It’s remarkable how well known these individuals are around the world – People outside of Europe could easily recognize most names on the list, or, at the very least, recognize most of the individuals' contributions.

Zooming in on the modern period, we see the rise and dominance of the U.S., as well as the relative decline of France, Germany, and Italy.

Here comes the fun chart, the 20th century. Towards the very end we see the rise of South Korea and Brazil. Fifteen South Koreans made the list of the 20th century. The six of them that were born before the 1970s worked in politics or business (e.g. Ban Ki-moon, Park Chung-hee). Everyone else was born in the 1990s and worked in entertainment (mostly k-pop stars).

Similarly, of the 24 Brazilians that made the list, 21 were athletes or coaches, spanning from Garrincha (1933 - 1983) and Pele (1940 - ) to Neymar (1992 - ).

Will the future of our globalized cultural arena be dominated by k-pop stars and Brazilian soccer/football players?

The Missing Businesspeople

Perhaps I live in too much of an information bubble, but I was expecting more businesspeople to appear on the list, especially the one that’s zoomed in on the 20th century. (All the buildings and programs are named after the Rockefellers and the Carnegies! Half of the headlines today involve a Bezos or a Musk!)

Surprisingly, of the 5,100 people most famous people since 1500 (51 decades x 100 people each decade), only 39 (or less than 1%) are in business. Below are the top 10 most famous businesspeople: (I italicize the names of those alive today to highlight the present-bias introduced by the underlying Wikipedia traffic data as well as the construction of the HPI)

| Rank | Name | HPI | Business |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bill Gates | 86 | Microsoft |

| 2 | Howard Hughes | 85 | Aircraft (likely more famous for producing Hollywood films) |

| 3 | Pierre de Coubertin | 85 | The Olympics |

| 4 | Oskar Schindler | 85 | Manufacturing (likely more famous for inspiring the eponymous movie) |

| 5 | Cecil Rhodes | 84 | Mining (likely more famous for the recent political controversies) |

| 6 | Warren Buffet | 84 | Berkshire Hathaway |

| 7 | John D. Rockefeller | 84 | Standard Oil |

| 8 | Ingvar Kamprad | 82 | IKEA |

| 9 | George Soros | 82 | Investing (likely more famous for political controversies) |

| 10 | Aristotle Onassis | 81 | Shipping (likely more famous for being married to Jacqueline Kennedy) |

The other living people on this list of 39 include Vince McMahon (WWE, World Wrestling Entertainment), Sepp Blatter (FIFA), Carlos Slim (Grupo Carso), Muhammad Yunus (Grameen Bank), Tim Cook (Apple), Steve Ballmer (Microsoft, LA Clippers), Jeff Bezos (Amazon), and Mark Zuckerberg (Facebook).4 Given that the HPI has a strong present bias and that the billionaire class is a historically new concept, I expect the ranking for the 20th and 21st centuries to change in the future.

We’ve already established that fame in the era of mass media follows k-pop stars and Brazilian soccer players. Here, the winning formula for rich people to get famous seems similar – produce movies or buy sports teams.

Is it a good idea for rich people to become famous though? I used to think that fame draws too much unwanted attention, but in light of meme stocks, cryptocurrencies, and SPACs, businesspeople (especially those in consumer-facing sectors) could use a loyal following. The mechanism by which they scale their business (i.e. the Internet) is exactly what they would use to build a persona. Perhaps the reason we didn’t have famous businesspeople in the last century was that consumer-facing businesses couldn’t scale, and the scalable businesses didn’t need followers.

What Robert Shiller said about Bitcoin will likely apply in more and more business cases:

I think narrative is very important to the popularity of Bitcoin and other crypto-currency. Part of the reason that Bitcoin succeeded is that it fed into an anarchism narrative that government is unnecessary and untrustworthy. It fostered a narrative that young people have created a financial institution that is out of the government’s reach. That’s a powerful narrative. It strikes people as fun and exciting like any viral video does, although it isn’t a sign of the validity of Bitcoin’s core concepts.

The mystery component is also very powerful. People like mystery stories. And mystery stories generate their own news, such as when people come forward claiming to be Satoshi Nakamoto. The legend of Satoshi Nakamoto may live on for a long time.

In the Amusing Ourselves to Death version of our dystopian future, actors become politicians and businesspeople, while businesspeople and politicians become actors. They are all storytellers, after all!

The Missing Women

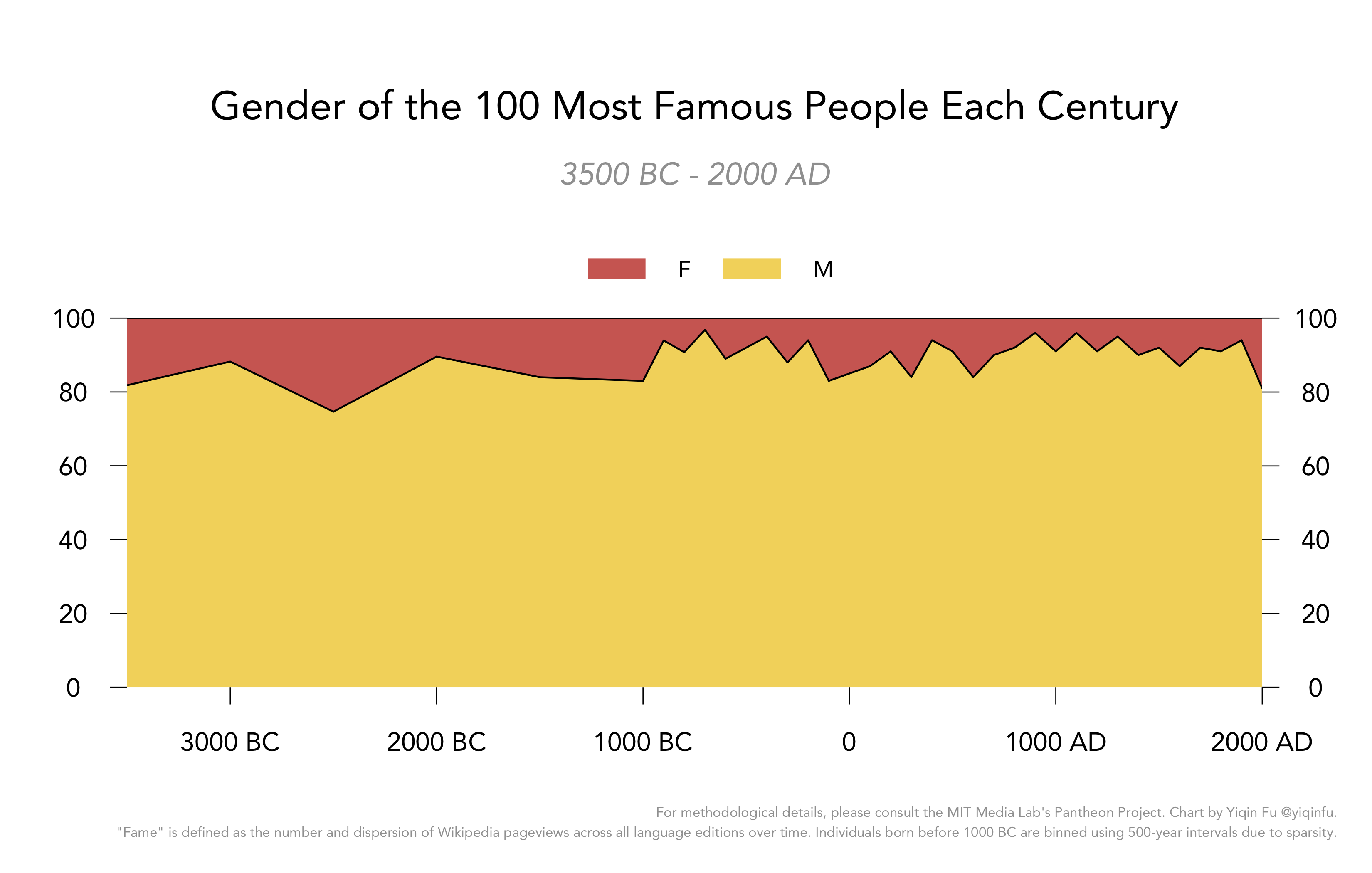

The changing roles women play in mainstream culture can also be seen in the data. Over the past five millennia, the share of famous women each century has stayed around 10-20%, but the stability of the aggregate numbers mask large compositional changes.

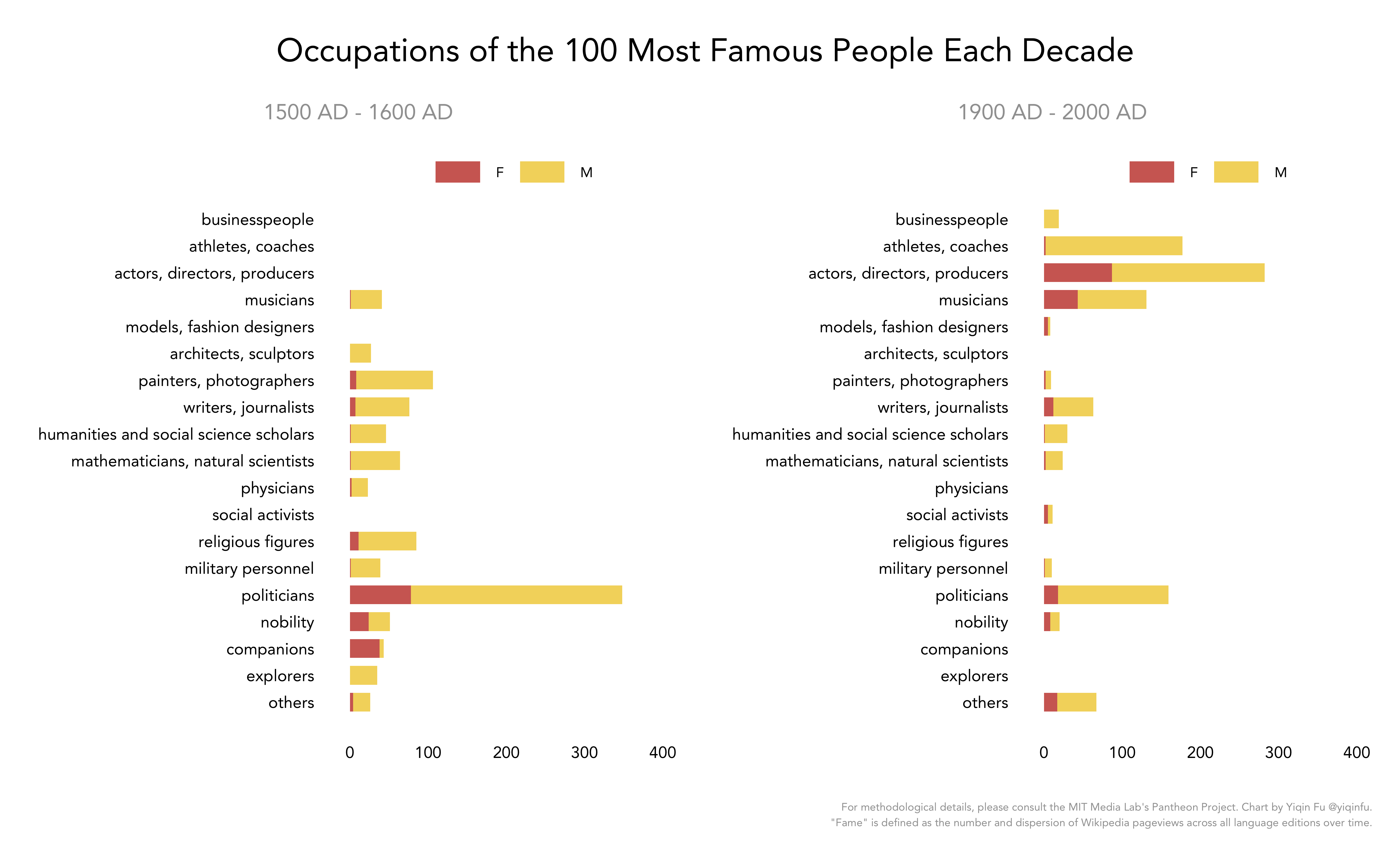

Below I plot the distribution of occupations in the 16th centuries and the 20th centuries, along with the gender split. Aside from the rise of the actor and athlete classes discussed in previous sections, the changing roles of women is also evident in the chart below.

A common occupation in the 16th century was “companions,” i.e. the companions of kings and emperors. Many well-known women from that period were empresses, but that category disappeared entirely in the 20th century. On the flip side, democratization also meant that political office became mostly elected as opposed to inherited. As a result, women, facing greater challenges when running for office, made up a smaller share of the politician class in the 20th compared to the 16th century.

Most of the gains women have made comes from being actors and musicians. It’s sad to see that not only have writers, humanities and social science scholars, and scientists lost ground in general, their share of women barely moved between the two periods. Athletes and coaches, making up almost a fifth of all famous individuals in the 20th century, are almost entirely male, as one would expect.

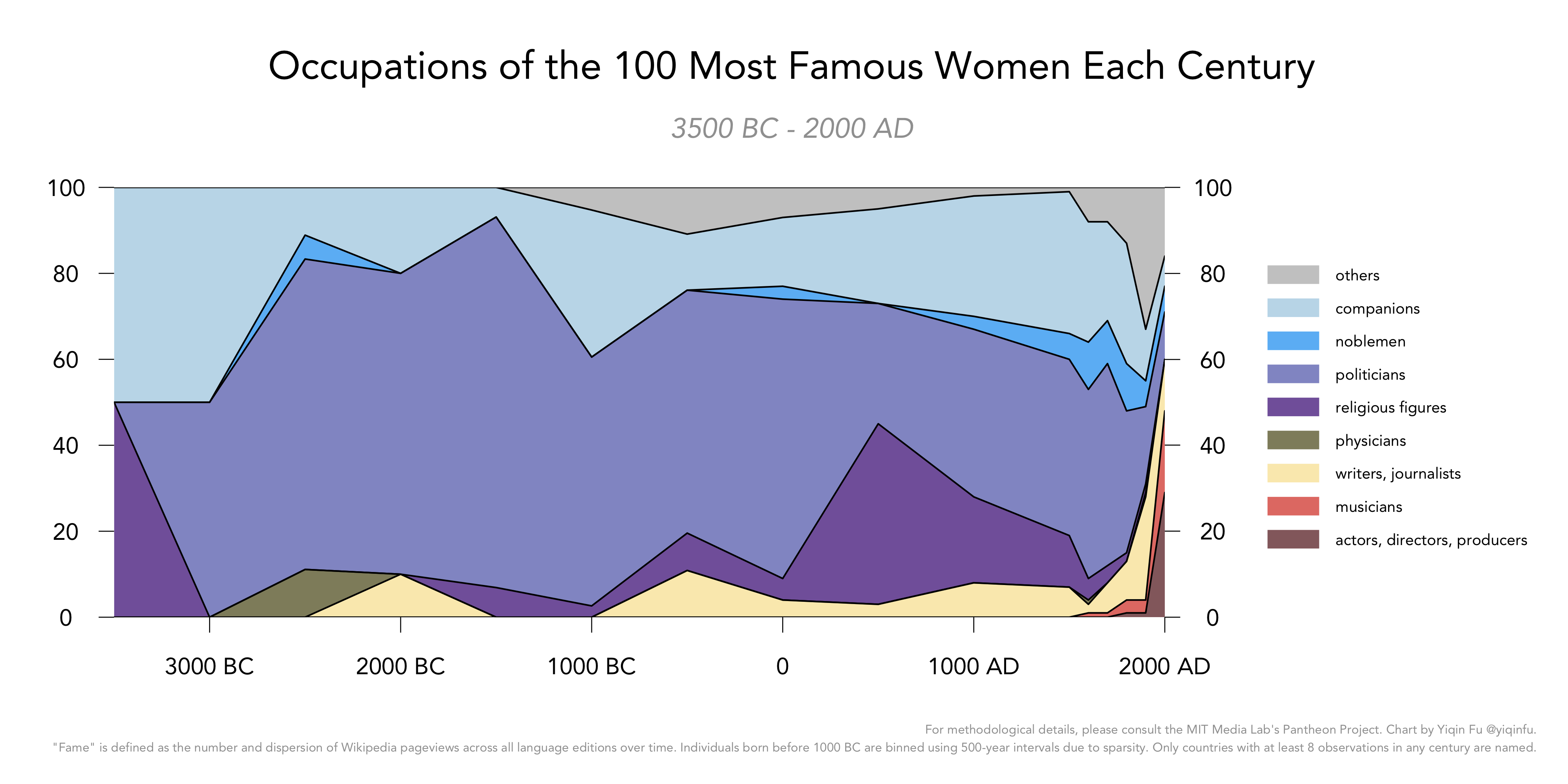

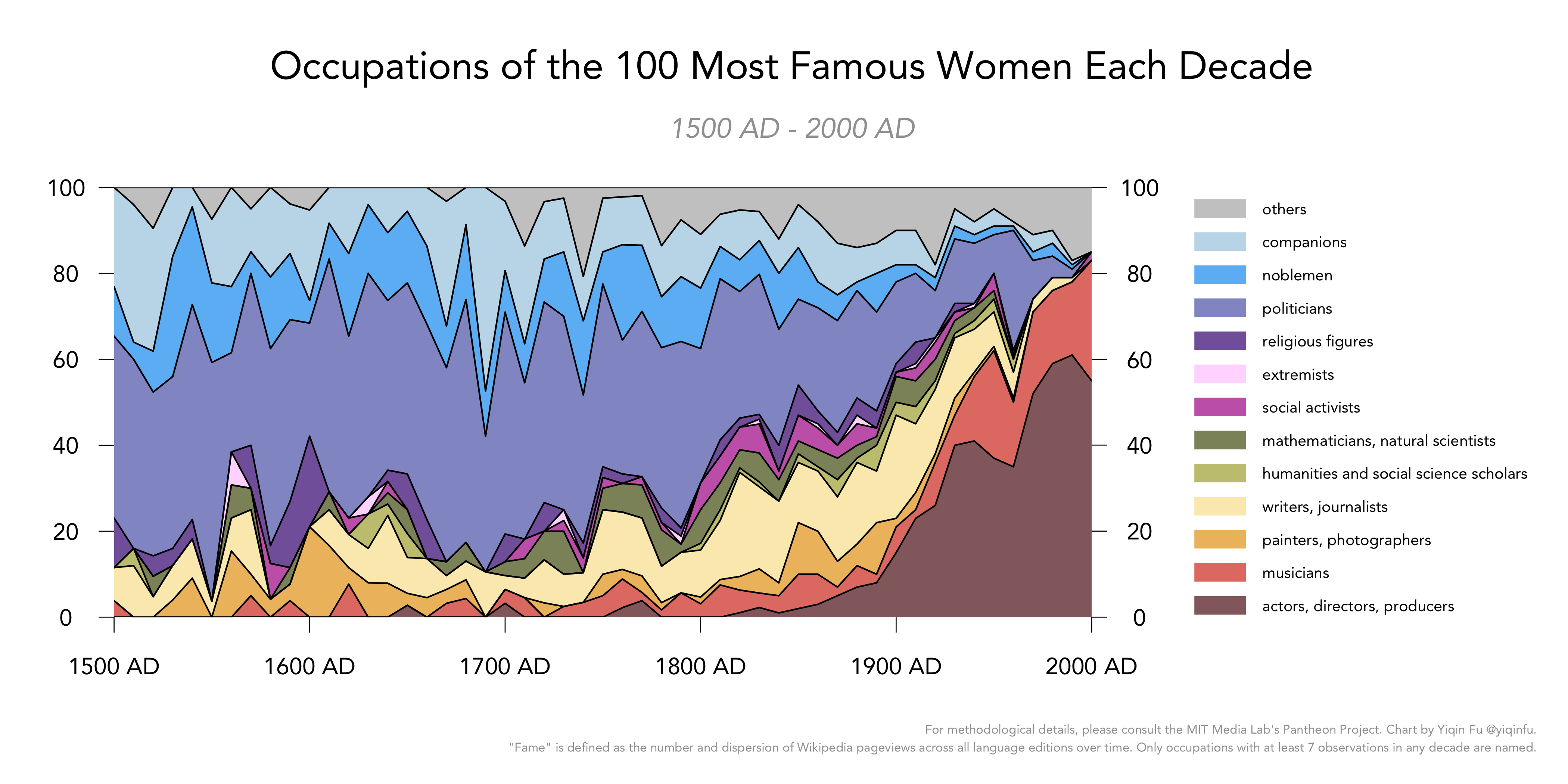

Below are prominent women’s occupation breakdown for the three different periods.

For much of human history, prominent women are “wives of prominent people” and “hereditary politicians”:

We start seeing scientists, writers, activists, and painters in the 17th and 19th centuries:

Given that 20% of famous people in the 20th century are actors, what do we make of the fact that 50% of famous women are actresses?

I conclude this section with the list of most famous women holding non-hereditary positions since 1500:

| Rank | Name | HPI | Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Marie Curie | 91 | mathematicians, natural scientists |

| 2 | Frida Kahlo | 90 | painters, photographers |

| 3 | Marilyn Monroe | 89 | actors, directors, producers |

| 4 | Agatha Christie | 88 | writers, journalists |

| 5 | Hilary Clinton | 88 | politicians |

| 6 | Rosa Luxemburg | 86 | social activists |

| 7 | Anne Frank | 86 | writers, journalists |

| 8 | Edith Piaf | 86 | musicians |

| 9 | Margaret Thatcher | 86 | politicians |

| 10 | Simone de Beauvoir | 86 | writers, journalists |

Hilary (1947 - ) and Thatcher (1925 - 2013) are much closer to our recent memory than the others on the list, so their HPI ought to be discounted more aggressively. Mother Teresa and Florence Nightingale are #11 and #12 on this list respectively.

The Enduring Appeal of Narratives

My main takeaway from this exercise is that narratives are so powerful that they’ve allowed good storytellers to have the kind of reach kings and emperors could only dream of.

Religious ideas spread through oral storytelling, and now actors and athletes are doing the same. (It would be interesting to study whether Hollywood and Netflix are replacing religion! See various discussions on the “fandom” culture.)

Storytelling’s production and distribution mechanisms have changed; the audience has massively expanded; the record-keepers are no longer the intellectual elites with ink pens but all human beings on the planet with Internet access. Fundamentally, though, haven’t we always been enthralled by a good story?

-

Another great paper (and dataset) on the topic of culture is Folklore by Michalopoulos and Xue, recently published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics. The authors code folk story motifs anthropologists have documented in 1,000 societies and create a measure of different historical societies' beliefs and preferences. ↩︎

-

The surge of Serbia around 500 AD is due to Constantine the Great (306 - 337 AD) and his relatives. ↩︎

-

Steve Jobs (Apple) is categorized as a “designer” by creators of the dataset and thus does not appear on my list of businesspeople. ↩︎