Do Men Have Less Intimate Friendships?

Jun 28, 2021 · 2434 words · 12-minute read

On Twitter and in popular academic media circles, many are making the claim that men, on average, have less intimate friendships than women.

I trace the claim back to the Oxford psychologist Robin Dunbar, who writes the following in his 2021 book Friends: Understanding the Power of Our Most Important Relationships:

Women’s friends are focused and intimate (individual relationships are more important than membership of the group), while men’s friendships are casual and involve what is almost an anonymous group (membership of the group is more important than the individual members themselves).

Here’s the New York Times columnist Elizabeth Bruenig more recently:

Ironically what I suspect killed intimate male friendships is misogyny: the full-on identification of emotion with femininity, such that sharing any kind of genuine feeling with another man came to be seen as feminizing to both. See a lot of this post-WWI.

Before we speculate about potential explanations, I thought we should first examine the quality of the descriptive evidence – Do men, on average, really have less intimate friendships than women? How are “friendships” and “intimacy” defined? What is the magnitude of the difference, and are there geographic, generational, and age variations?

Empirical Evidence Cited in Dunbar (2021)

I purchased the Dunbar book to look for supporting evidence. Unfortunately, the book provides a list of referenced academic papers for each chapter but doesn’t make inline citations – There’s no way for me to know which papers form the foundation of the claim about gender differences in the intensity of friendships. Given that I don’t work in evolutionary or social psychology, I could only skim the long list of papers and read the few that I think may be relevant.

Women More Willing to Tolerate Pain for Best Friends?

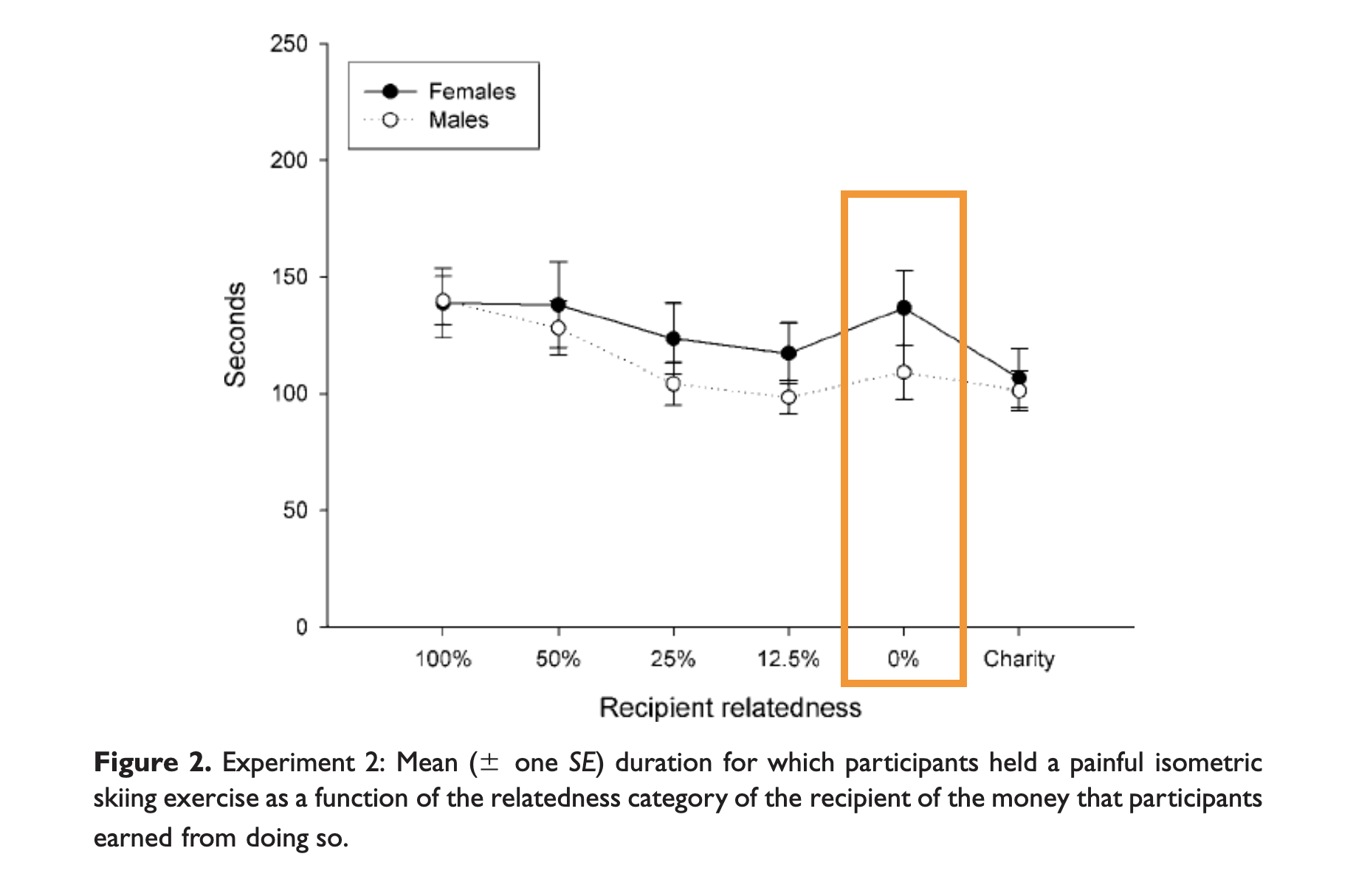

The first study I read was Kinship and Altruism: A Cross-Cultural Experimental Study (2007) by Madsen, et al., which Dunbar explicitly references in the main text of his book as evidence for the gender difference in intensity of friendships.

The main research question of the Madsen study is whether stronger kinship ties lead to more altruistic behavior. Researchers conducted lab experiments that tested for how long participates were willing to tolerate pain in exchange for financial payoffs sent to someone else. Under different experimental conditions, the recipient was randomly assigned as relatives with different levels of kinship ties to the study participants.

The main finding, that people are more altruistic towards closer relatives, was replicated across three experiments (two involving British college students and one involving South African villagers). However, the “best friend” experimental condition was present in only one of the three experiments (the “0% relatedness” column in the chart below), and the experiment was conducted on 40 University of London students whose mean age was 21 years old.

To establish solid evidence for gender differences in the willingness to endure pain for best friends, we probably have to conduct more experiments where 1) gender difference is the main research question and 2) the experimental subjects are more diverse.

Women Favor Dyadic Friendships, and Men Prefer Groups?

Gender differences in friendship structure could also serve as evidence for gender differences in the intensity of friendships – If women socialize one-on-one with friends and men socialize in groups, we might argue that men’s friendships are less intimate.

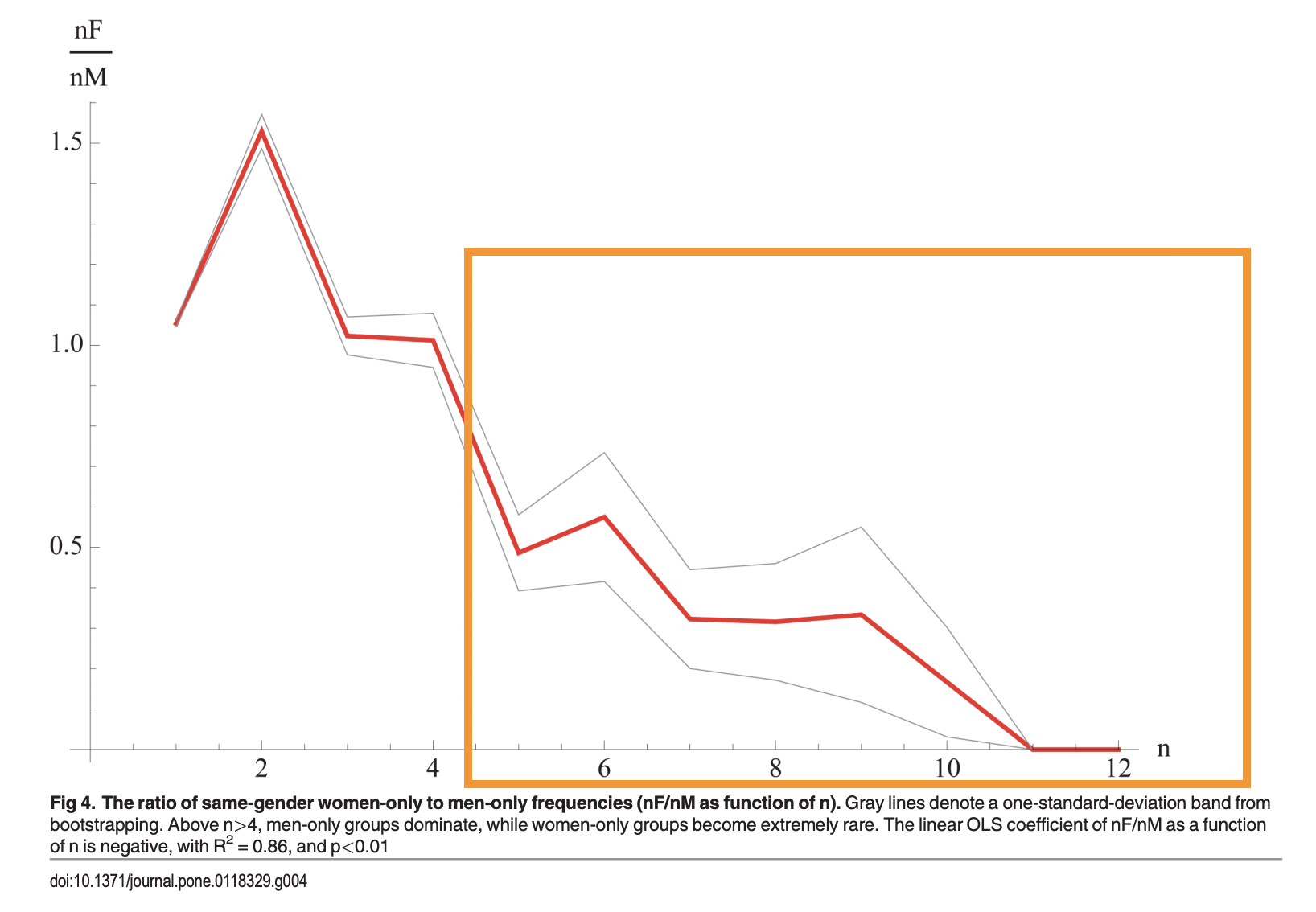

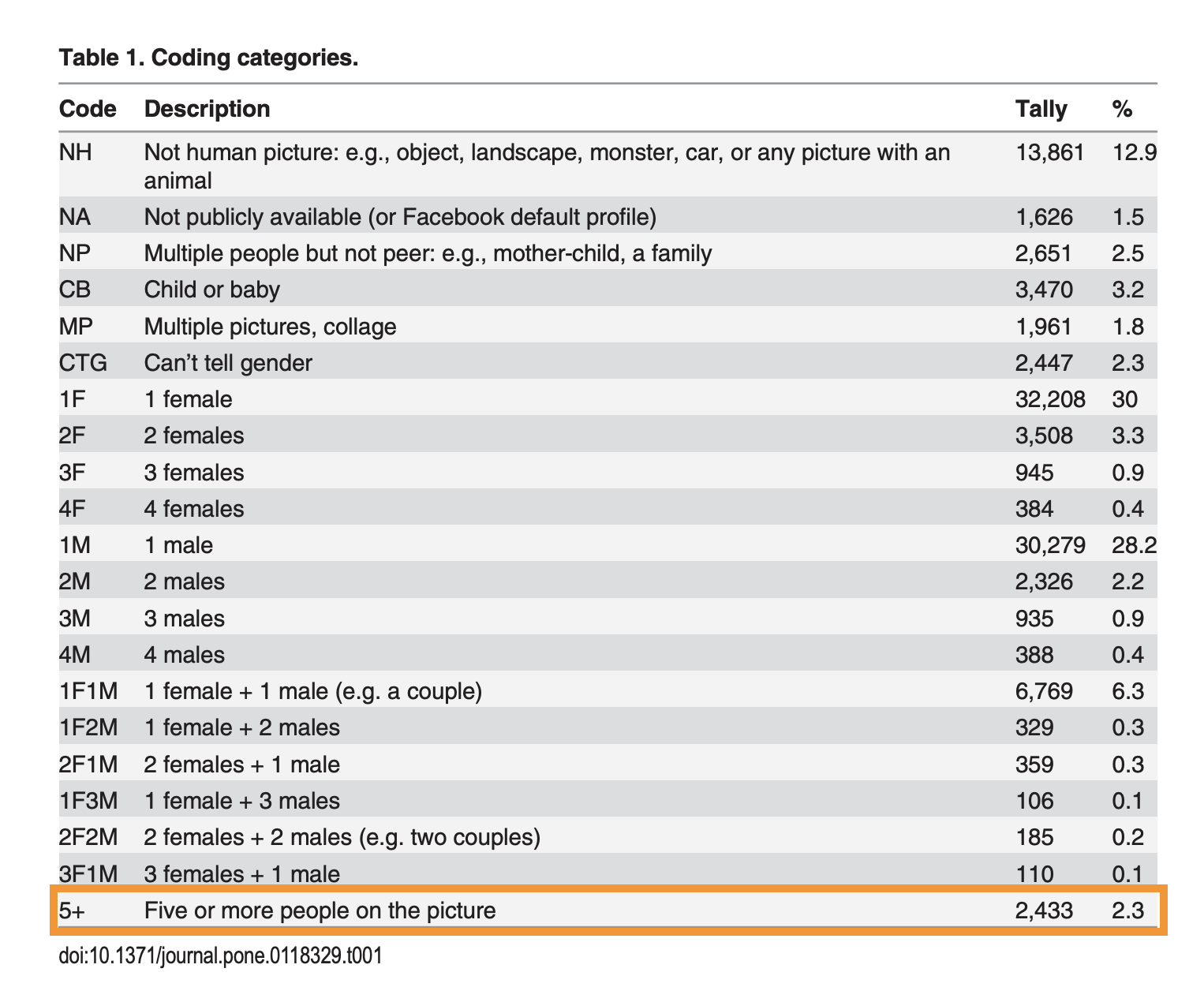

Again, given that I don’t know which papers are cited for this claim, I skimmed the references section of the Dunbar book and read a paper whose title seemed relevant: Women Favour Dyadic Relationships, but Men Prefer Clubs: Cross-Cultural Evidence from Social Networking (2015) by David-Barrett, et al.

In this study, researchers randomly collected Facebook profile photos and coded the gender composition of the people pictured (only counting pictures featuring peers). The central claim that “men prefer clubs” rests on the following figure:

My interpretation of this figure is that for profile photos that feature more than five people, there are a lot more all-male photos compared to all-female ones.

The pattern is interesting (and certainly fits my prior assumption about the type of people that chooses to have profile photos featuring 5+ people), but I don’t know how closely it’s connected to the study’s title and main conclusion. My concerns are twofold:

-

External validity: Profile photos are what people put out for others to see, so even if the study is internally valid (i.e. “men are pictured in larger groups than women”), it might be that men prefer dyadic relationships just as much as women but perceive there to be social returns to being seen online in these club photos.

-

Internal validity: The study claims that men are pictured in larger groups, but we are not getting a comparison of

P(clubs|male)andP(clubs|female)but some evidence forP(male|clubs)instead.

We can do some back-of-envelope calculations to back out the quantities of interest, and the authors of the paper do report detailed descriptive statistics of the profile photo dataset:

Only 2.3% of the people in the dataset have more than five people in their profile pictures (i.e. P(clubs)=0.023), so the difference between P(clubs|male) and P(clubs|female) is going to be really small regardless of the precise value we assign to P(male|clubs).

There seems to be a small difference in the share of FF and MM photos (3.3% vs. 2.2%), but I don’t know how to make further interpretations without access to the raw data. Overall, the evidence for gender differences seems quite weak.

Men and Women Have Different Cellphone Conversations?

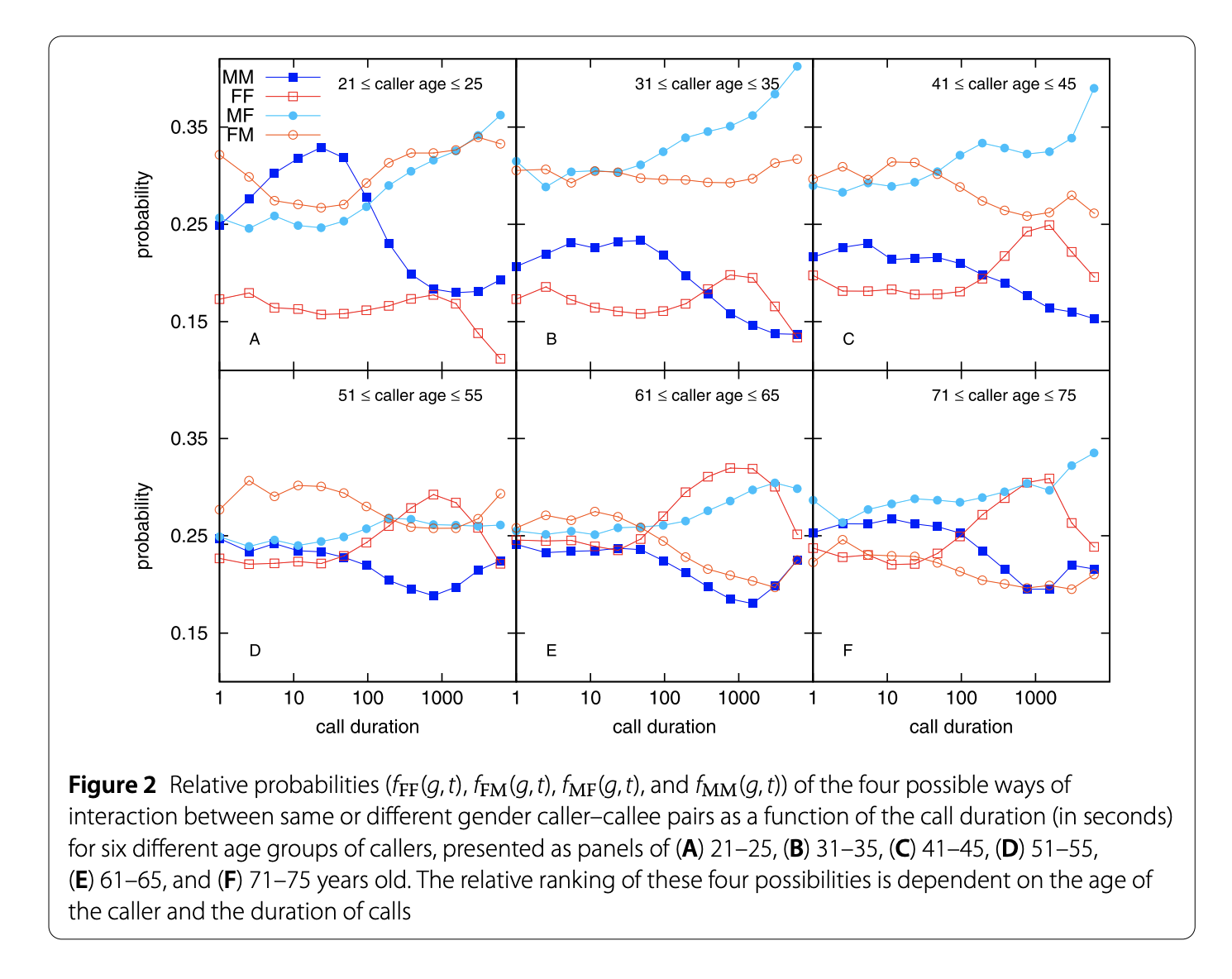

The third Dunbar reference I read, and the one that looked the most promising, was Quantifying Gender Preferences in Human Social Interactions Using a Large Cellphone Dataset (2019) by Ghosh, et al.

I was excited about this paper because we were finally getting behavioral data (cellphone call logs) that were somewhat related to our research question (whether the intimacy of friendships varies by gender). Lab experiments and Facebook profile photos are useful, but what’s better than actual call metadata from a “European mobile service provider” that contained information on the duration of the call, as well as the demographics of the individuals involved?

If I got my hands on this dataset, I’d compare the concentration of callees for each caller by call frequency and cumulative call duration, essentially constructing an inequality index. If male callers' contact with callees is more dispersed than female callers, then we’d have suggestive evidence that female friendships are more intimate.

Of course, we’d worry that 1) the frequency and duration of calls aren’t positively correlated with the intimacy of the relationship; 2) calls to non-friends may bias the result (e.g. men likely make more business calls than women, skewing the concentration index downwards). Overall though, I think an analysis of frequency and duration distributions at the caller level would point us in the right direction.

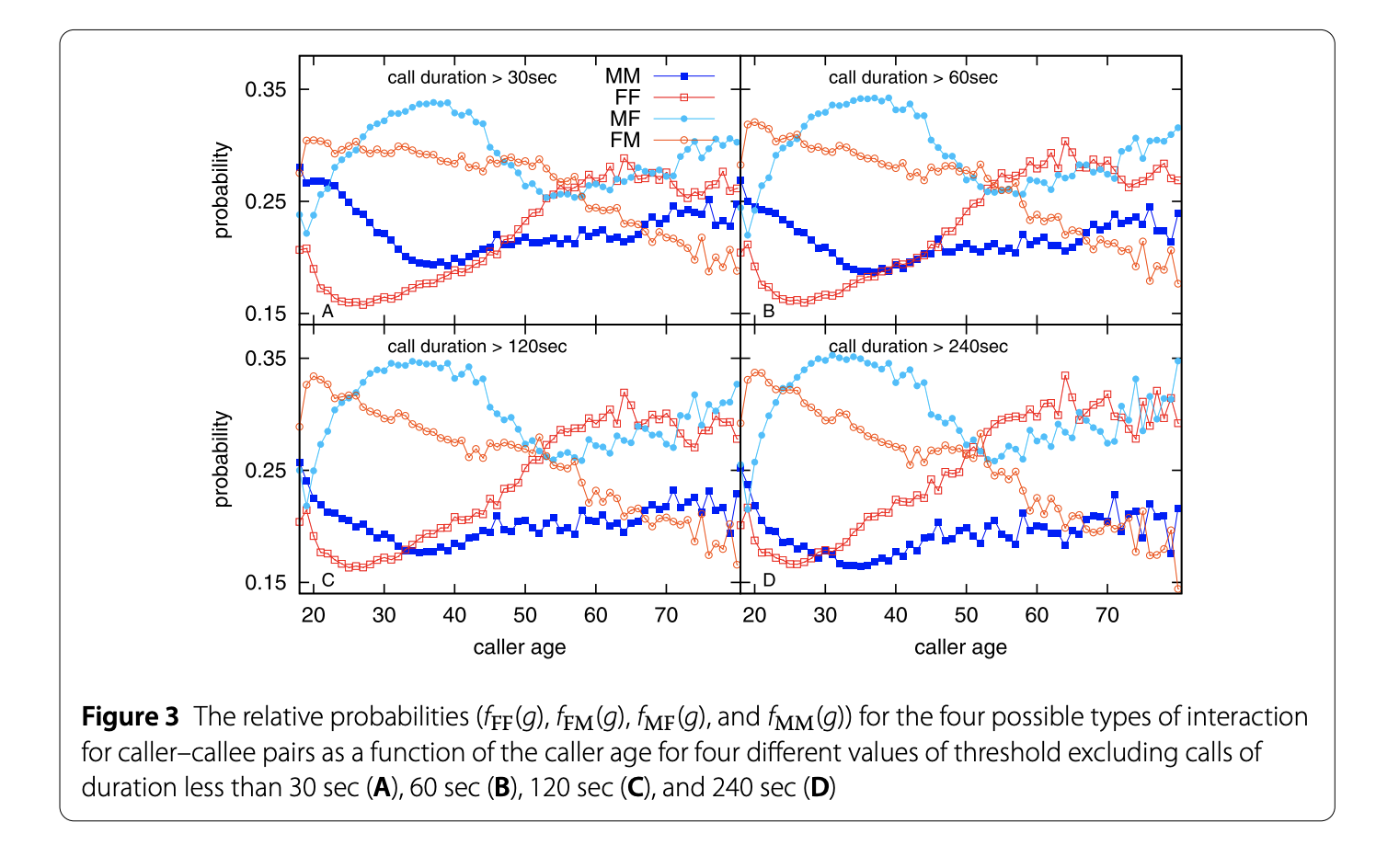

Unfortunately, the authors of the paper chose to focus on the conditional probabilities in gender composition by call duration and caller age. The main conclusion of the paper is that the caller-callee gender pairs varies by call duration and caller age.

For example, the figure above shows that conditional on the call being 20 seconds and the caller being in their early 20s, the call is most likely between two men (panel A).

Similarly, the figure above shows that conditional on the call being longer than four minutes and the caller being in their 30s, the most likely gender composition is MF, followed by FM, FF, and MM (panel D).

Looking at Panel D, we might speculate that the divergence between the FF line (red square) and the MM line (blue square) as age increases is evidence for gender differences in the intimacy of friendships. However, since the data is analyzed at the call level rather than the caller level, we cannot be sure what is driving the relative rise of the FF pairing.

In fact, the authors go on to attribute the relative rise in FF calls to mothers and grandmothers calling their daughters (rather than women calling their friends), although I can’t find a figure in the paper that shows the intergenerational nature of these calls.

Since the dataset contains information on the age and gender of callers and callees, I think the cleanest way to answer our question would be to only include calls to those within five years of the caller, and plot the concentration of callees by frequency and cumulative duration. The way the authors of the paper sliced the data isn’t particularly helpful here.

Similarly Weak Evidence from Other Studies

Through Internet searches and friend recommendations, I came across three other relevant studies.

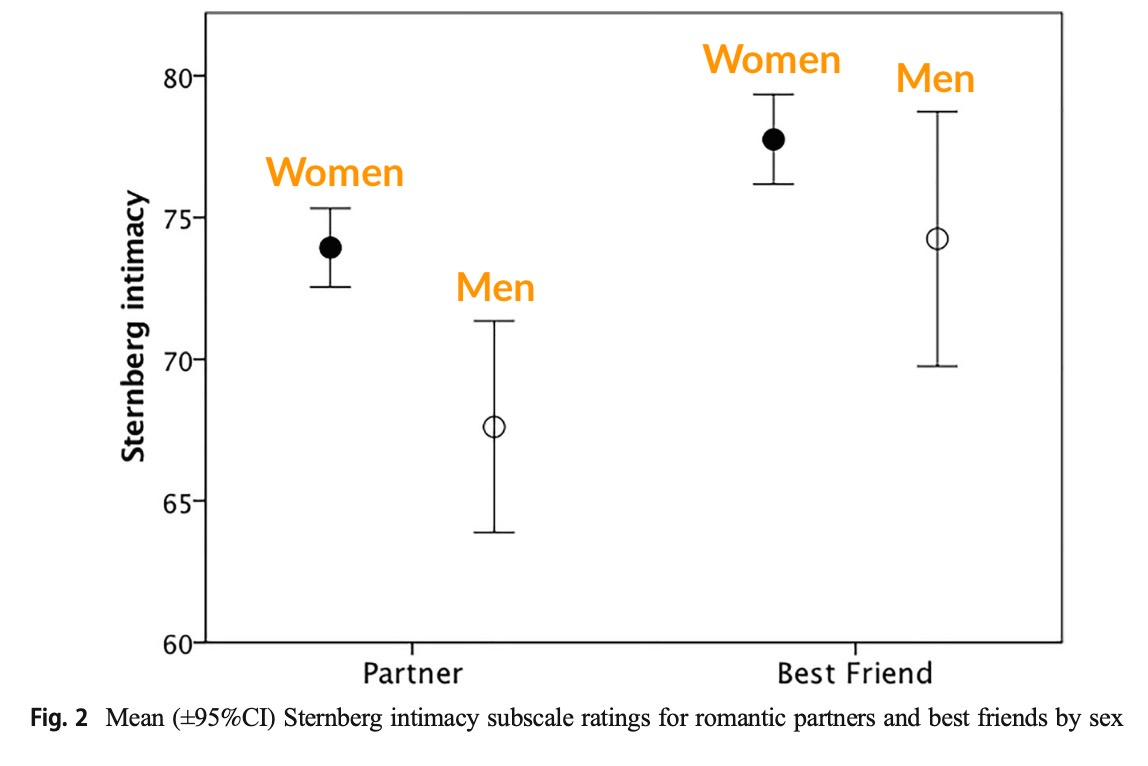

In Sex Differences in Intimacy Levels in Best Friendships and Romantic Partnerships (2021), Pearce et al. asked an online convenience sample to rate their romantic partner and best friend on an intimacy scale. Questions included:

- I’m able to count on X in times of need.

- I’m willing to share myself and my possessions with X.

- I feel that X really understands me.

Unfortunately, the online convenience sample skewed heavily female:

- 260 participants (201 female; mean age 31 years)

- Mean length of a romantic partnership 10 years; mean length of a a best friendship was 13 years

- 54%) resided in Europe, 42% in North America

Given the small number of male participants, we can’t be sure that men rated their best friends as less close than women. Curiously, both men and women (on average) rated their best friends as closer than their romantic partners.

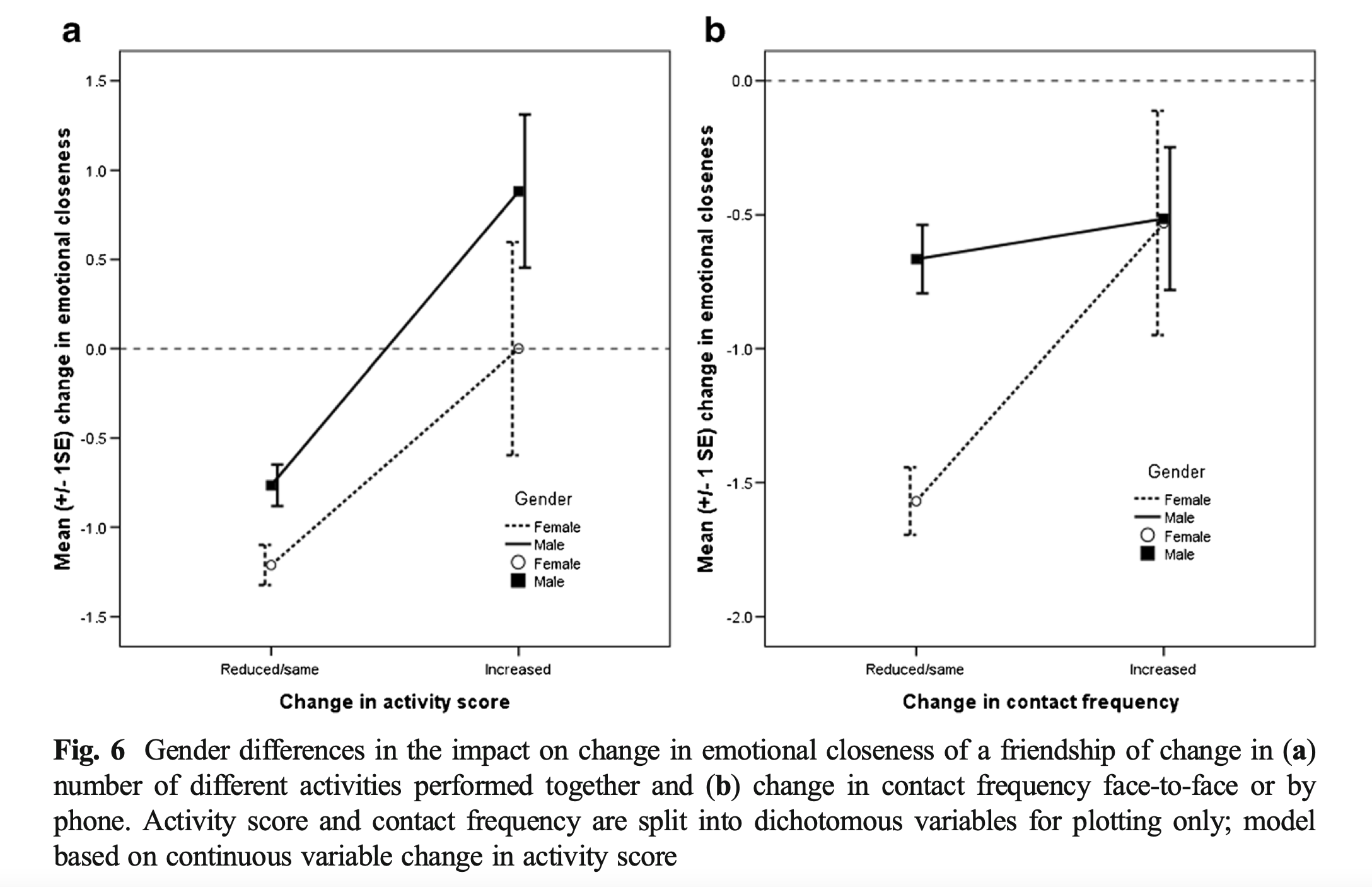

The fifth study I read was Managing Relationship Decay: Network, Gender, and Contextual Effects (2015) by Roberts and Dunbar. In this study, participants were surveyed in person at three time points (T1: month 1, T2: month 9, T3: month 18) about the level of emotional closeness they felt towards each friend as well as their frequency of contact and activity. Here’s the comparison of emotional closeness between T1 and T3, conditional on activity/contact frequency as well as gender:

Among men, doing more things together seems associated with closer emotional bonds, whereas for women, less contact is associated with greater emotional distance.

The study would generalize much better, however, if the participants weren’t just 30 British high schoolers from one area (mean age 18 years, range 17 to 19). It’s perhaps not so bad to use an undergraduate or high school sample in many cases, but given that adult friendships (or “post-school” friendships) are so different from school ones, we can’t make sweeping claims about “men and women” based on a survey involving only 18-year-olds.

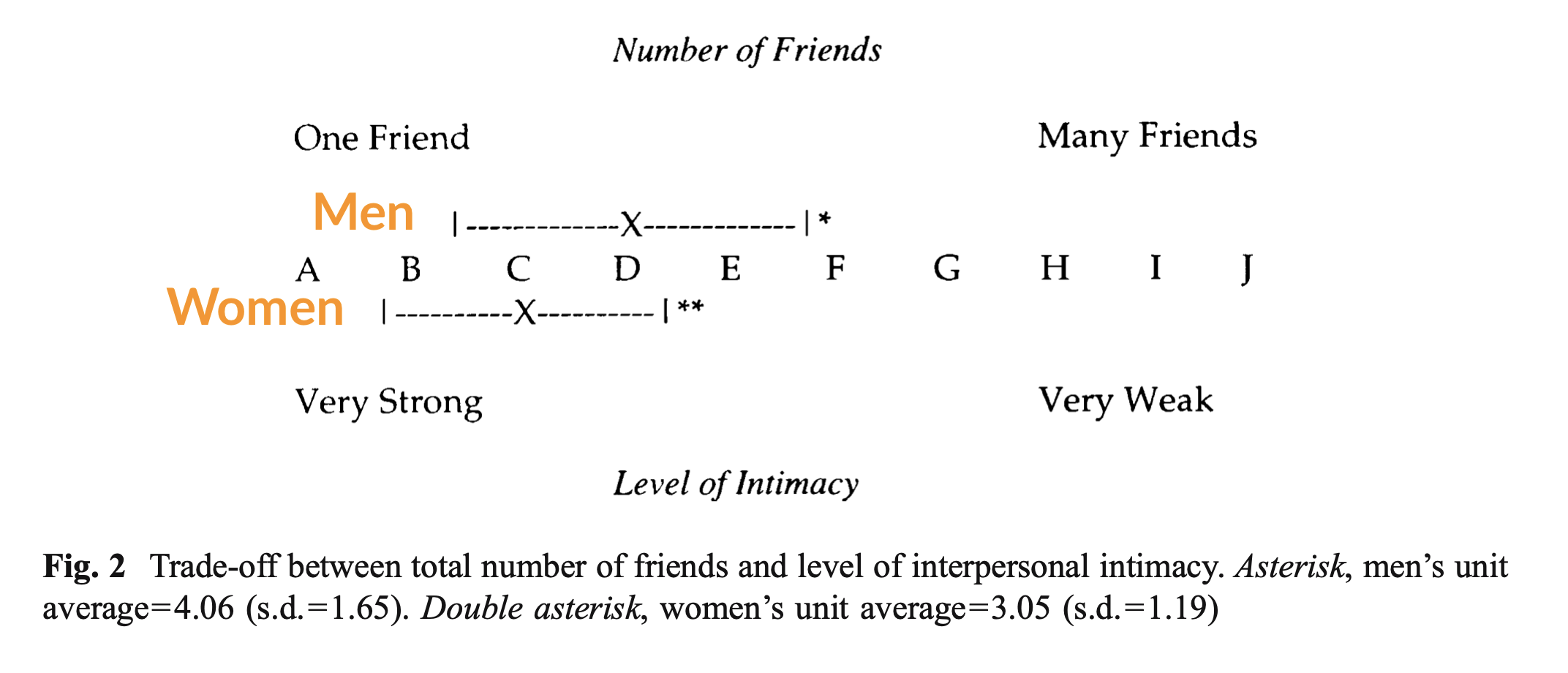

In Asymmetries in the Friendship Preferences and Social Styles of Men and Women (2007), Vigil asked 251 undergraduates (mean age 19 years) to select their ideal number of friends and ideal level of intimacy, with the two dimensions presented on a forced constraint scale. Here we see some evidence that women prefer fewer but closer friendships, but I have no idea what a unit increase on this scale means and whether men and women interpret the scale the same way.

The Ideal Design and Existing Survey Data

Assuming that the papers I read do form the basis of Dunbar’s argument, his claim that men have less intimate, more “clubby” friendships is not supported by good evidence.

In research, the first question we ask is always “what would the ideal design be.” If we are interested in gender differences in intimate friendships, my ideal research design would be a diary study where participants are asked to record their hourly activities for a week, including the names of people with whom they did the activities.

Do such studies already exist? The only “diary-based” dataset I can think of is the American Time Use Survey conducted annually by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The phone survey asks American adults to recall what they did in the previous day.

Unfortunately, the BLS' coding of activities doesn’t allow us to quantify the duration and the structure of people’s social activities – “playing sports” could be done alone, with one other friend, with many friends, with children, etc. Given that gender may act as a confound depending on which activity we include, a male-female comparison of plausibly “social” activities wouldn’t be very helpful.

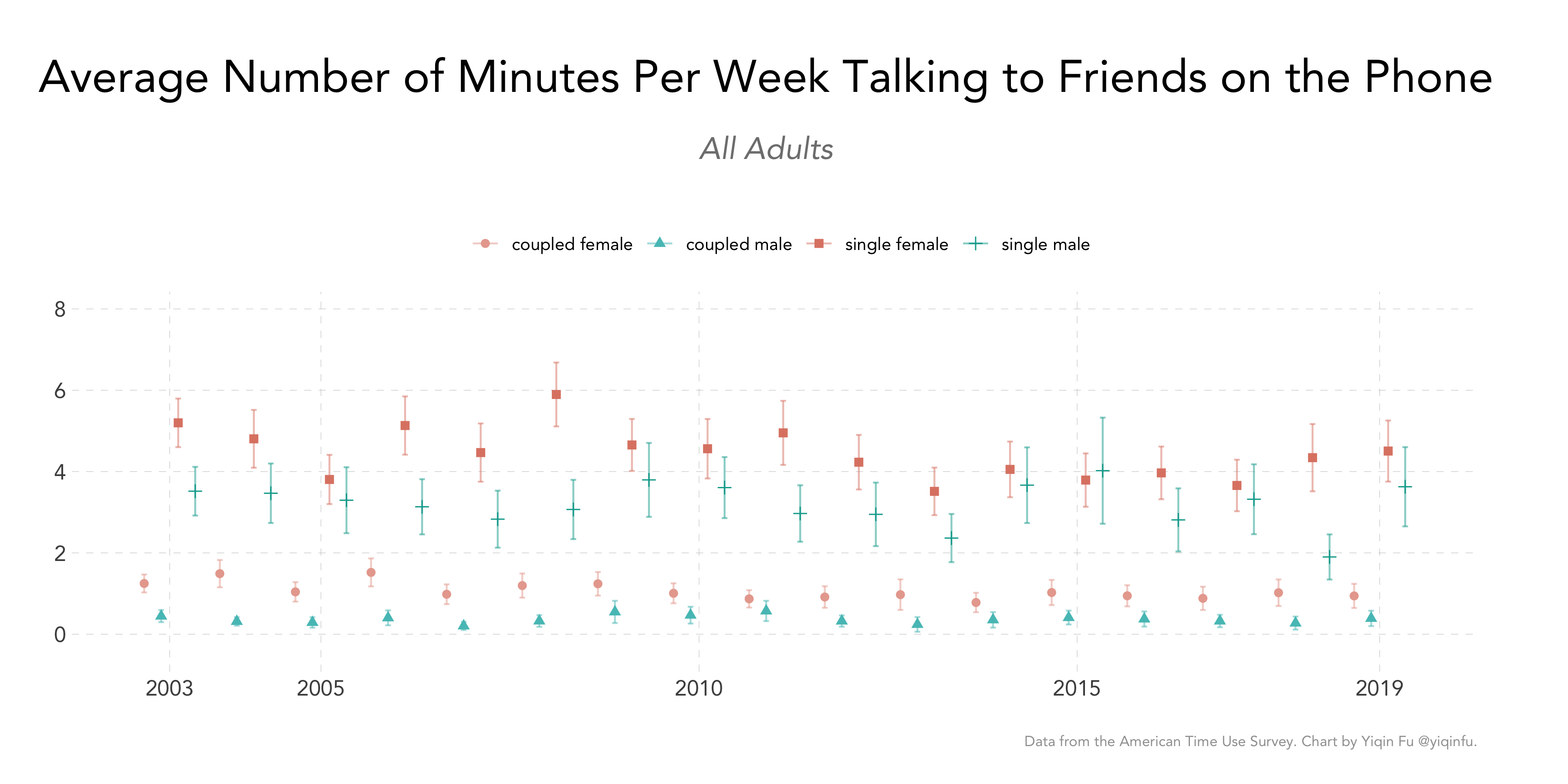

The survey, however, does contain an item that mentions “friends” explicitly: item #160102 “telephone calls to/from friends, neighbors, or acquaintances.” Again, the duration of phone calls may not perfectly correlate with the strength of relationships, and people socialize with friends much more in person. But the patterns in this dataset are nonetheless interesting to explore. Here’s the average number of minutes spent talking to friends on the phone for all Americans:

Four observations:

- Coupled people talk to friends on the phone a lot less, echoing Dunbar’s claim that gaining a romantic partner leads one to lose two friends;

- The Internet or social media has not replaced phone calls as a way to connect with friends – the number of minutes spent on the phone remained constant throughout this period of dramatic changes in communication technologies

- The absolute level, though, is much lower than I expected. The people I know likely spend an average of 60 minutes per week talking to friends on the phone, and I’d have guessed 20 to 30 for the general American population. But the American Time Use Survey says that the number is less than five. Perhaps most people live very close to their friends and always meet up in person?

- Gender differences are present both among single and coupled people, although the absolute magnitude is small, given that the averages are only a few minutes a week for the entire population.

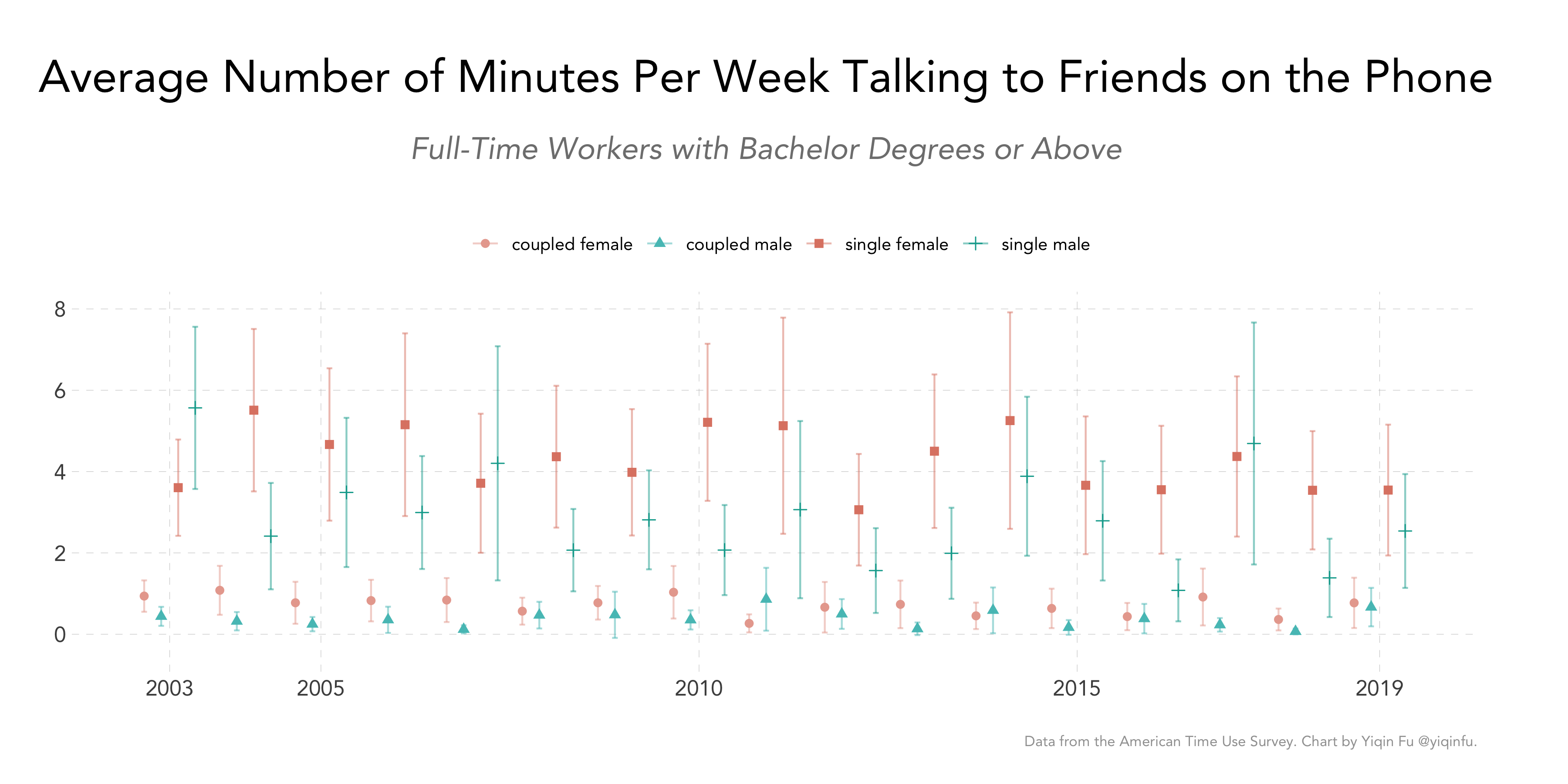

I wondered if the gender difference was largely compositional (women being much less likely to work, etc.), so I subset the data to those with bachelor’s degrees who worked more than 40 hours a week.

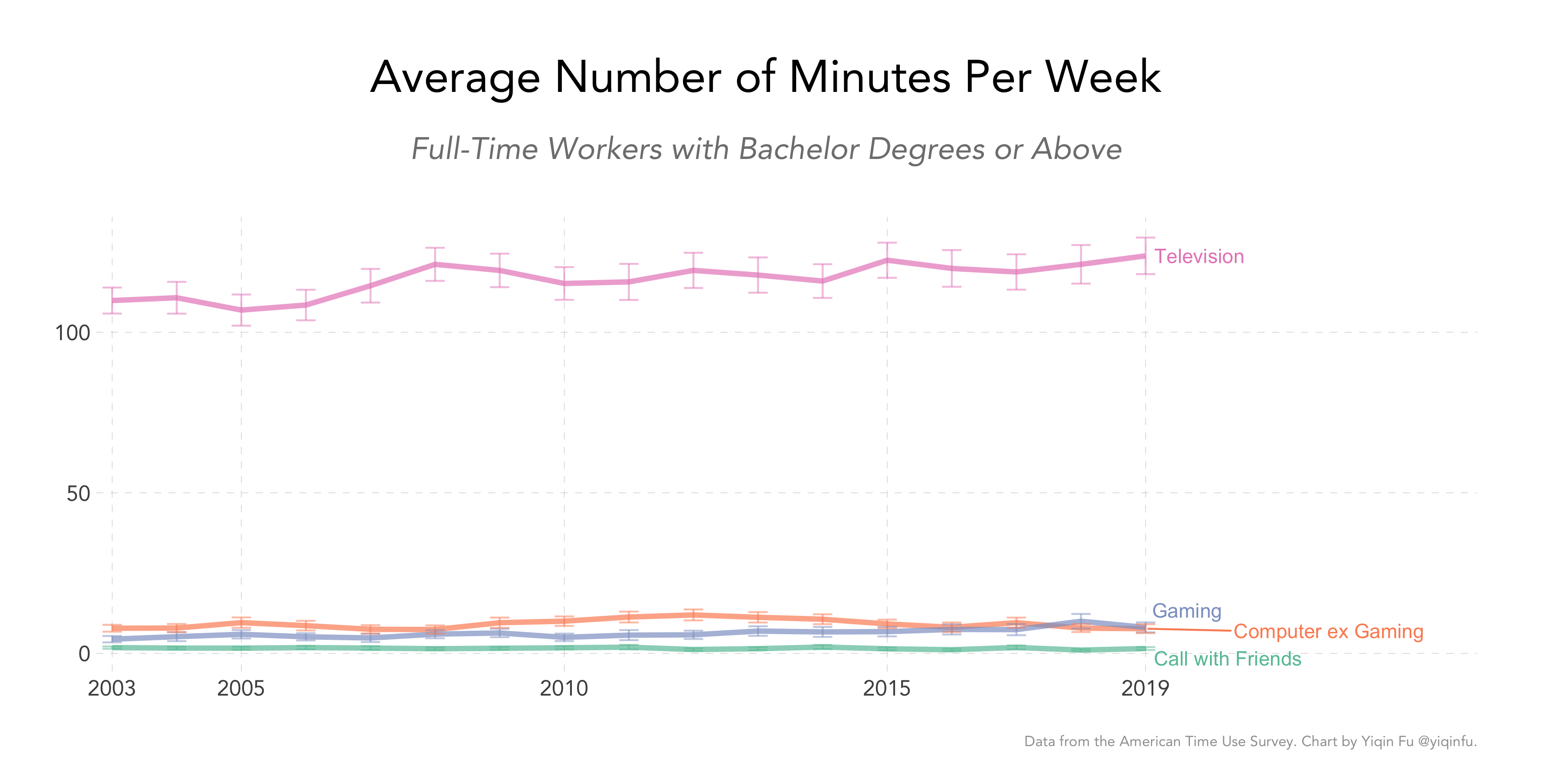

The gender differences are much harder to see now. And the regression coefficients on gender don’t point to a clear conclusion, either, once we control for other demographic characteristics. The magnitude of the difference (one or two minutes per week) is tiny if we zoom out and look at how Americans spend their leisure time more generally:

Conclusion

Measuring the intimacy of friendships is hard, and we simply don’t have enough evidence for the stark gender differences frequently mentioned in the popular discourse. It would be great if we could move away from lab experiments involving 20 undergraduates and examine behavioral data or contemporaneous “diaries” (activity logs) instead.

Even if rigorous studies in the future do find gender differences, though, it is important to note that they’d be differences in averages. The distributions for men and women may still overlap a great deal.