The Hinton Intellectual Dynasty

Jul 11, 2023 · 1666 words · 8-minute read

This post summarizes the long lineage of intellectuals in Geoffrey Hinton’s family. Hinton (1947-)’s many associations include backpropagation, AlexNet, Turing Award, Google Brain, Sutskever, LeCun, etc.

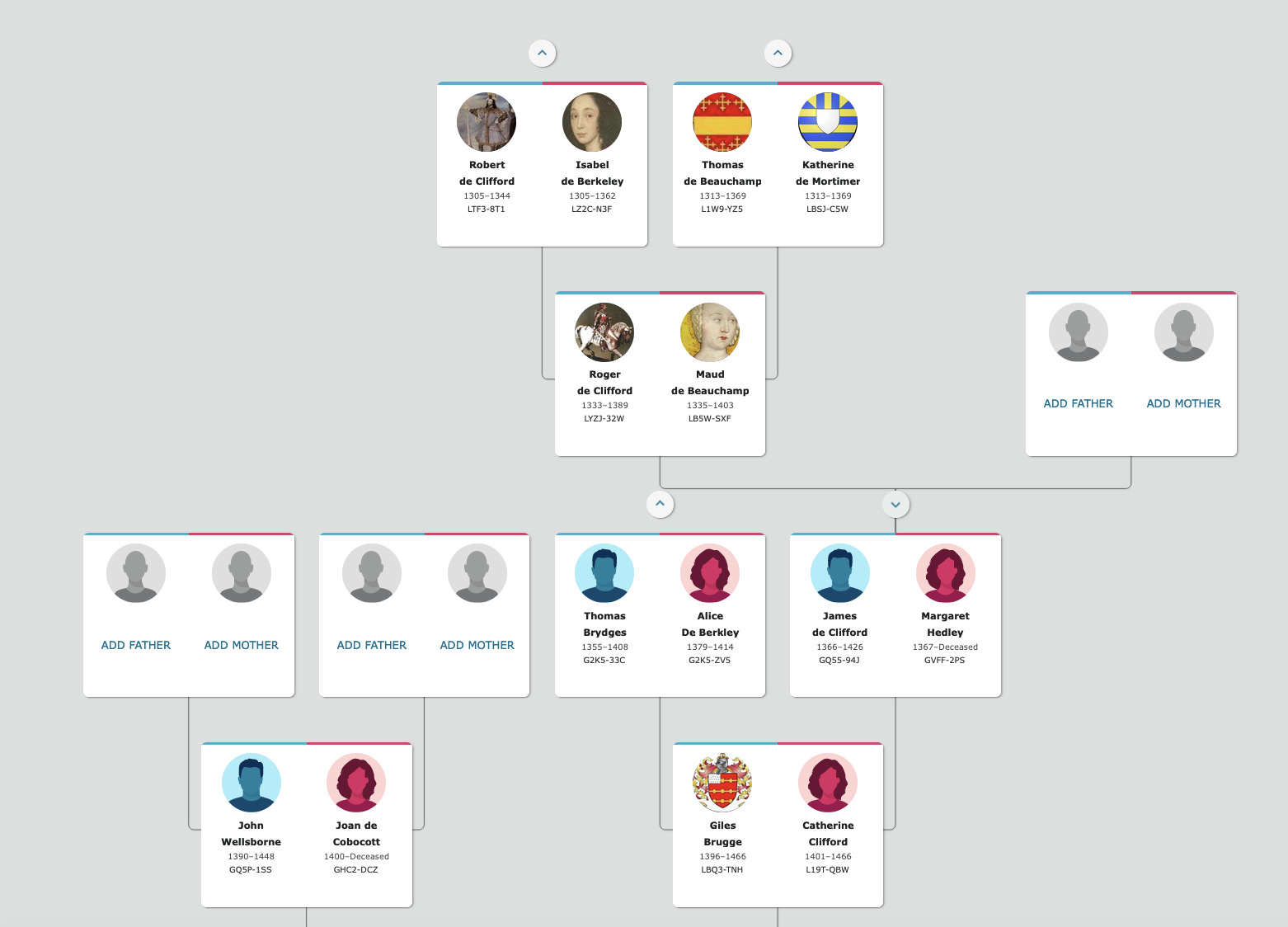

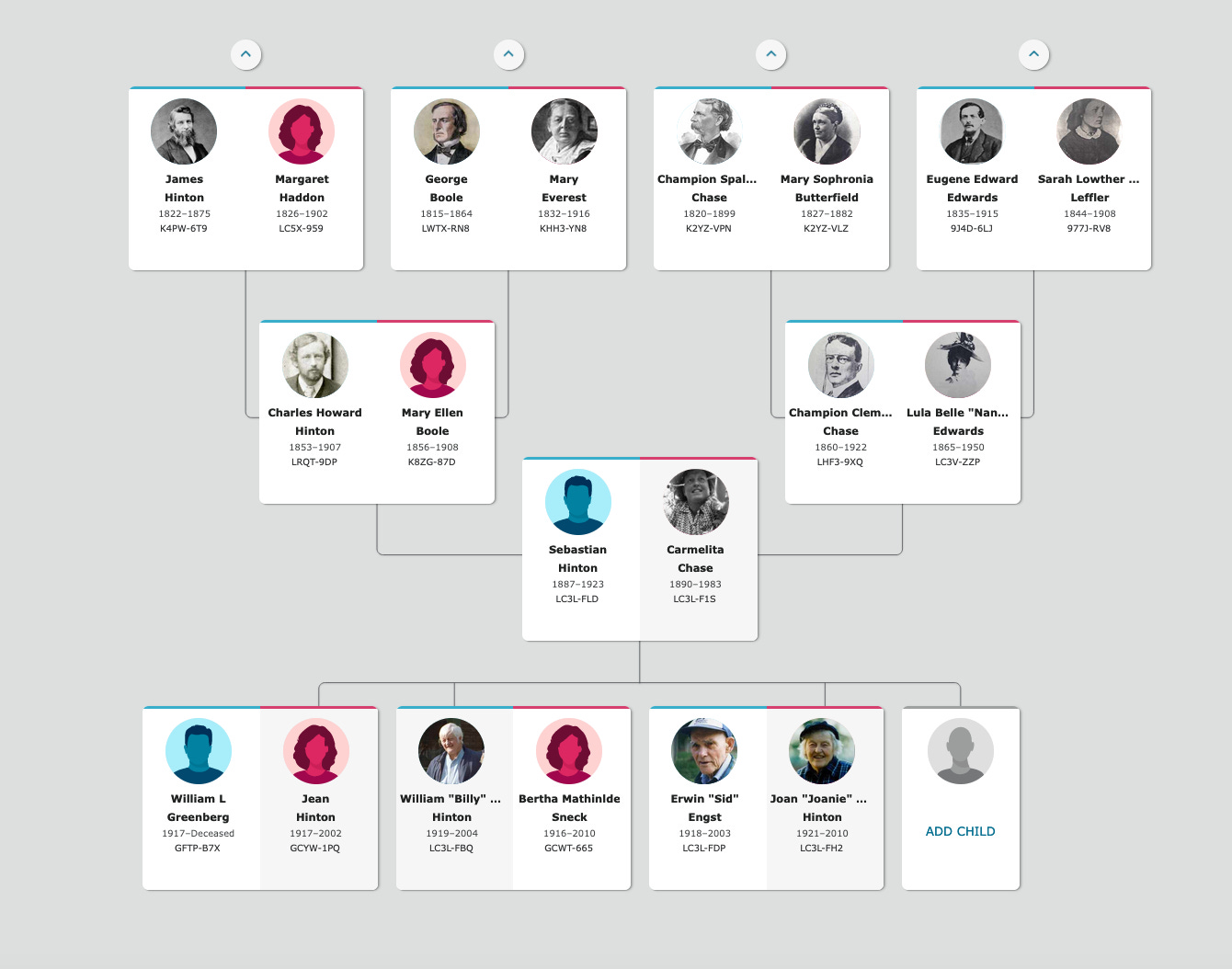

Notable people within four generations:

-

His great-great-grandfather, or father’s father’s mother’s father, was George Boole (1815-1864), the mathematician and logician after whom Boolean logic is named. (LLM critics find it ironic that the current approach is a departure from the Boolean, symbol manipulation-based approach to AI.)

-

Not exactly an intellectual, but: George Boole’s wife Mary Everest Boole (1832-1916), also a mathematician, was the niece of George Everest (1790-1866), the British surveyor after whom Mount Everest was named (in English), making him Geoffrey (Everest) Hinton’s 3rd great-granduncle and the relative for whom he’s named.

-

His great-grandfather, or father’s father’s father, was Charles Howard Hinton (1853-1907), a mathematician who studied high-dimensional geometry and wrote science fiction. Jorge Luis Borges referenced his name in three short stories. Here’s an excerpt from Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius:

It’s extremely fitting (and poetic!) that a descendant of both the inventor of Boolean logic and a science fiction writer admired by Borges lead humanity’s best effort so far towards general machine intelligence.

Not household names everywhere, but of particular interest to people with connections to socialism:

-

His first cousin once removed, with whom he shares the same great-grandfather, was Joan Hinton (1921 - 2010). Joan, a nuclear scientist who studied under Enrico Fermi, left the Manhattan Project after Hiroshima to start a dairy farm in China. When I shared the story in Chinese, I learned that she’s extremely well-known among intellectual circles there — She was the first non-PRC citizen to receive permanent residency; Yang Chen-Ning was a close friend when they were both working with Fermi and spoke about their friendship at length at his 100th birthday celebration in Beijing in 2021; Soong Ching-ling arranged for Joan to move to China in 1962 and later named her son (heping, or peace).

-

Another one of his first cousin once removed was William Hinton, Joan’s bother. William was a Marxist intellectual who met with Zhou En-lai five times, attended the Chongqing negotiations between the KMT and the CCP, wrote books on village land reform, and was, at various points of his life, designated by the American and the Chinese governments as friends and as traitors — The English- and Chinese-language descriptions of his life talk about entirely different periods, and you should read both! Both Joan’s and William’s partners and children have also been heavily involved China’s political development in the 20th century, often ending on different sides in different times even if their views remained the same.

-

William Hinton’s daughter Carma Hinton, Geoff’s second cousin once removed, made perhaps the most famous and most widely streamed China documentary of the 20th century, The Gate of the Heavenly Peace, about 1989 Tian’anmen. In fact, she was the first Hinton I knew!

If you keep going up the tree, you’ll find:

-

Great-great-grandfather James Hinton (1822 - 1875), surgeon, of Reading, England

-

Great-great-great-grandfather John Howard Hinton (1791 - 1873), Baptist minister, of Oxford, England

-

First cousin five times removed (John Howard Hinton’s cousin) Jane Taylor (1783 - 1824), poet who wrote the verse of Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star!

These people, despite having Wikipedia pages, are not noted for their kinship ties to Geoff Hinton or other extended members of the family. It would be cool (and easy now with LLMs!) to traverse through all people profiles on Wikipedia1 and build a kinship network. Perhaps Geoff Hinton tops the list as the person with the highest eigenvector centrality (i.e. the person with the highest quality of ties)?

If you keep going up the tree (thanks to the extensive grassroots data collection effort on familysearch.org), you’ll find many lords, barons, princesses, etc. I’m not familiar with genealogy statistics to know what the baseline expectation is for the average person alive today to have ties to lords 8 or 10 generations back. Supposedly we are all descendants of Genghis Khan if you go far back enough? What’s the right way to calculate the extent to which someone’s lineage deviates from the average person’s?

My Chinese readers kindly noted that the Cade Metz book Genius Makers has a sketch of Hinton’s lineage (omitted here for brevity) as well as his academic journey:

It was expected that he would one day follow his father into academia. It was less clear what he would study. He wanted to study the brain. His interest, he liked to say, was sparked while he was still a teenager, when a friend told him the brain worked like a hologram, storing bits and pieces of memories across a network of neurons, much as a hologram stored bits and pieces of its 3-D image across a strip of film. It was a simple analogy, but the idea drew him in. As an undergraduate at King’s College, Cambridge, what he wanted was a better understanding of the brain.

The trouble, he soon realized, was that no one understood much more than he did. Scientists understood certain parts of the brain, but they knew very little about how all those parts fit together and ultimately delivered the ability to see, hear, remember, learn, and think. Hinton tried physiology and chemistry, physics and psychology. None offered the answers he was looking for. He started a degree in physics but dropped out, convinced his math skills weren’t strong enough, before switching to philosophy. Then he dropped philosophy for experimental psychology. In the end, despite pressure to continue his studies—or perhaps because of that pressure, brought down by his father—Hinton left academia entirely.

When he was a boy, he had seen his father as both an uncompromising intellectual and a man of enormous strength—a Fellow of the Royal Society who could do a pull-up with one arm. “Work really hard and maybe when you’re twice as old as me, you’ll be half as good,” his father had often told him, without irony. After graduating from Cambridge, with thoughts of his father hanging over him, Hinton moved to London and became a carpenter. “It wasn’t fancy carpentry,” he says. “It was carpentry to make a living.”

That year, he read The Organization of Behavior, a book written by a Canadian psychologist named Donald Hebb that aimed to explain the basic biological process that allowed the brain to learn. Learning, Hebb believed, was the result of tiny electrical signals that fired along a series of neurons, causing a physical change that wired these neurons together in a new way. As his disciples said: “Neurons that fire together, wire together.” This theory—known as Hebb’s Law—helped inspire the artificial neural networks built by scientists like Frank Rosenblatt in the 1950s. It also inspired Geoff Hinton. Every Saturday, he would carry a notebook to his local public library in Islington, North London, and spend the morning filling its pages with his own theories of how the brain must work, building on the ideas laid down by Hebb. These Saturday-morning scribbles were meant for no one but himself, but they eventually led him back to academia. They happened to coincide with the first big wave of investment in artificial intelligence from the British government and the rise of a graduate program at the University of Edinburgh.

In these years, the cold reality was that neuroscientists and psychologists had very little understanding of how the brain worked, and computer scientists were nowhere close to mimicking the behavior of the brain. But much like Frank Rosenblatt before him, Hinton came to believe that each side—the biological and the artificial—could help the other move forward. He saw artificial intelligence as a way of testing his theories of how the brain worked and, ultimately, understanding its mysteries.

The Hinton family’s intellectual success over at least four or five generations could be attributed to several factors:

-

They have been spared the worst of the World Wars (moving to the U.S.; spending time in Latin America) and have rarely been targeted for their work (unlike some in the Eastern Bloc);

-

Each family typically had four or five children;

-

Assortative mating, although it is unclear how much should be attributed to genetics and how much to environmental factors.

Persistence stories are fascinating. Wealthy Italian families from the 15th century are still wealthy today. Even in China, where experienced violent, class-based revolutions, the elite families of the day have returned to the top. Two opposing forces will be at play in the future: a decrease in the number of children per family and an increase in the similarity of wealth, income, and education levels among people who form families.

Persistence in intellectualism is especially curious. It is almost certain that wealth, as well as the ability to make a career in politics and entertainment, will persist for decades to come — in 2100, there will likely be celebrities named Streep or Depp, politicians named Kennedy or Trump, and heirs named Zuckerberg or Musk. But intellectual persistence is much harder — the evaluation scheme is much more objective than politics or entertainment (you can’t be famous for the sake of being famous in science, and in the arts as well, if you look at the very long run), and, more importantly, one’s outside options look more and more attractive as society becomes wealthier and the returns to cognitive ability increase. The value system, instilled via perhaps both nature and nurture, needs to be particularly strong for intellectualism to persist.

My questions:

-

Are there families like the Hintons in other places? I can only think of the Browder family of Russia and America and the Liang-Lin family of China and America.

-

How long can an intellectual dynasty last? And if AI solves (or at least accelerates or changes) science in a meaningful way, what will the next Hinton be doing?